For anyone with a keen interest in heritage train travel, the excursions offered by the Ffestiniog and Welsh Highland Railways are just about as good as it gets.

Starting from a picturesque harbour station at Porthmadog, the Ffestiniog offers scenes of tranquil pastures and lush woodlands, before making a vertiginous climb around the side of Snowdonia. The Welsh Highland route, meanwhile, zig-zags past the quaint town of Beddgelert, scaling steep hillsides before passing beneath the famous castle walls at Caernarfon. Both journeys can take your breath away.

Such undulating routes are only made possible through the use of some dependable locomotives. The Ffestiniog is the only railway in the world to operate double-ended Fairlie steam locomotives, which are dextrous enough to pull carriages through the narrowest mountainside spaces. The Welsh Highland has other requirements: unforgiving 1-in-40 gradients need powerful Beyer-Garratt NG/G16s weighing more than 60 tonnes to deliver passengers to their final destination.

These locomotives are central to the appeal of the Ffestiniog and Welsh Highland Railways and they are the source of enormous pride. The locomotives are cared for at Boston Lodge, a 150-year-old workshop just outside Porthmadog. Here, 30 employees and volunteers carry out a complete range of restoration and maintenance activities to ensure that the Fairlies, Beyer-Garratts and a host of other locomotives and carriages are fit for purpose. Such is the diverse array of skills at Boston Lodge that the facility has also started making locos and carriages for other heritage railways. Past projects include two vehicles built to replicate Darjeeling Himalayan Railway examples and the construction of replica Pickering carriages for the Welshpool and Llanfair Light Railway.

Staff have also built a carriage based on the concept of the parlor car used on the Sandy River and Rangeley Lakes Railroad in Maine. The original design was modified to suit the customer’s specifications – including the addition of a kitchen.

“Boston Lodge is totally unique,” says works manager Tony Williams. “Heritage locomotives and carriages can be restored and repaired on site whilst we are also able to produce modern locomotives and stock. There is no other facility anywhere else in the world that can carry out the range of services that we do.

“The key to the operation is the skills of the people. We train them ourselves. They are a product of the many years’ experience that we have here and they continue a long tradition of innovation and quality. It helps that they are all steam fanatics – they have boundless enthusiasm.”

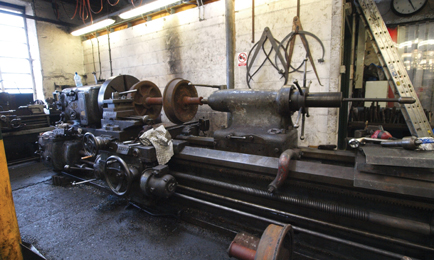

A tour inside Boston Lodge reveals a scene more in keeping with a railway workshop from the early 20th century. Workers kitted out in greasy overalls man bulky and noisy lathes, while others have descended pits below vast boiler structures armed with spanners and wrenches. But there’s also plenty of modern kit, such as ultrasonic testing equipment used to measure structural integrity. The work being carried out is the perfect marriage of old and new, with giant steel structures engineered to the finest of tolerances.

The facility is a veritable Aladdin’s cave. In the surrounding buildings, there are piles of axle-boxes, transmissions, oil burners, you name it – nothing gets thrown away. “But it’s not just about copying and patching up,” insists Williams. “We also design, machine and build new locomotives in totality, as required.”

It’s a busy place. Boston Lodge has just finished rebuilding a Bagnall 3023 loco that originally worked at a mine in South Africa. The frames and boiler have been completely rebuilt, along with additional parts such as a spark arrestor. The Bagnall has been tested on the Welsh Highland Railway, before being returned to the Lynton and Barnstaple, where it will resume trips along the Devon coast.

Talking shop: Boston Lodge is home to several locomotives

Well equipped: Tools of the trade for Boston Lodge technicians

Brush strokes: New carriages are painted by hand for a quality finish

“Our reputation is highly regarded both nationally and internationally, and our services are frequently in demand from local business,” says Williams. “We are also regularly commissioned to carry out repairs on industrial machinery. Two of our most recent contract projects involve adapting trucks for use at a local slate quarry and engineering industrial mixers for a Caernarfon-based firm.”

A Double Fairlie loco is in the process of being converted from oil to coal. Meanwhile, two Hunslet locomotives that originally operated at the nearby Penrhyn Quarry are undergoing a similar package of work before being returned to steam on the Ffestiniog Railway.

Next door, in the carriage frameshop, a third-class carriage new-build for the Welsh Highland Railway is well under way at a cost of £100,000. All the major components including the roof, ceiling panels, insulation, glazing, lights, seats and tables are put together in-house, before the completed unit is lovingly painted.

The next big package of work is a rebuild of Welsh Pony, the fifth locomotive made for the Ffestiniog line, way back in 1867. Welsh Pony has had a hard life – going through numerous overhauls. But more recently it has been left exposed to the elements in North Wales, so the refurbishment is expected to be quite an undertaking. Around £100,000 has been spent on forensic analysis alone.

There’s no doubt that what comes out as a finished job from Boston Lodge certainly gets put through its paces. Each Garratt does 15,000 miles a year on the Welsh Highland Railway, while the Fairlies clock-up 9,000 miles a year on the Ffestiniog line. “That’s amazing amounts for a heritage railway,” says Williams. “They have interchangeable bogies and boilers which means they can be easily maintained.”

Williams is a trained driver on both railways and it’s clear that he thoroughly enjoys his time in the locomotives’ cabs. “I love going out in both the Garratts and the Fairlies,” he says. “It really offers me the chance to feel how the locomotives are performing and to second-guess what work needs to be done. I can feel it when a locomotive is tired – you notice all the niggly little faults developing.”

On the footplate, it is the fireman’s job to produce the required amounts of steam for the journey. That means shovelling up to 1.5 tonnes of coal on each trip. The driver concentrates on signals and the anticipation of gradients, working out when to accelerate and when to slow down.

“The hardest part of the driver’s job is keeping concentration,” says Williams. “You need to have a wide view of what is going on around you. You have to keep an eye on the engine, the train carriages behind you, what’s going on on the footplate, and what’s in front of you. You need to have been a fireman to become a driver – and you must have the right mindset.”

In total, the Ffestiniog and Welsh Highland lines have 100 full-time staff, but more than 1,000 volunteers are vital to the smooth running of the railways. Some help in the workshops, others on-board the trains or at the stations. Williams says they don’t struggle to attract people who are keen to play their part. “There will always be an interest in railways. We get lots of youngsters volunteering. They might go off for a few years when they start a family, but they always tend to come back. We never lose them.”

On the engineering side, Williams says that both railways could always do with more qualified volunteers. “We could do with more help from older engineers who have experience in industry,” he says.