International shipping rarely gets noticed. The sector only hits the headlines when there is an accident or a hijacking.

But those big boats are fundamental to making our modern life happen. Without shipping, there would be no global economy. No intercontinental trade, no imports and exports of affordable manufactured goods and food, no transport of raw materials.

The downside is pollution. You’ll almost certainly notice shipping if you live near a major port, because you’re suffering the pollution. In Hong Kong for example, sulphur dioxide (SOx) from maritime emissions is thought to be responsible for almost 400 deaths a

year. Last year the number of polluted days in Hong Kong increased by 28% to

303 and experts are looking out to sea for the culprit.

On a global-scale it’s known that international shipping is responsible for 3% of all CO2 emissions, 10% of the sulphur emissions from all types of fossil fuels and also nearly 30% of global releases of nitrogen oxides (NOx).

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) is addressing the problem with the introduction of environmental legislation that aims to reduce the SOx, NOx and CO2 emissions from ships.

The first phase of the legislation is to set up Emissions Control Areas, coastal waters that contain shipping lanes and ports. The ECAs are being introduced in stages around the world. The second phase is to then restrict emissions from international waters. The second phase could take effect from 2020, if planned changes are ratified as expected by the IMO in 2018.

There are several ways shipowners can reduce their emissions, such as switching to ultra low sulphur diesel or methanol fuels, or using scrubbers to remove pollutants from their exhaust. But James Ashworth, lead consultant with Singapore-based oil and gas consultancy, Tri-zen International, says those options have problems that prevent them from being widely implemented. He says: “Ultra low sulphur diesel is as expensive as it is on petrol station forecourts. Can you imagine fuelling a ship with it?”

“Methanol has its own set of problems. it’s very hygroscopic. It can be abused, but is toxic.”

“Scrubbers are expensive and their longevity is unproven in maritime applications. They’re fine in power stations, but the instrumentation and components are not practical in a corrosive maritime environment.”

The most viable option, says Ashworth, is liquid natural gas (LNG). LNG is increasingly being considered as a fuel for a wide range of transport applications because it has virtually no sulphur content and produces low NOx. However, LNG is not without its technical and commercial barriers. LNG is more difficult to process and store because it requires refrigeration and compression. A fundamental difference is that LNG containers need to be larger than existing fuel tanks because the energy density of LNG is lower than diesel and they have to be insulated.

Ashworth says that 80% of ships cannot be retrofitted for LNG simply because they do not have room for the containers. “They’ll have to be scrapped,” he says. “The big winners will be shipbuilders and engine makers. It could lead to a resurgence in shipbuilding, particularly in Europe.

“Anyone operating LNG ships will see the benefits, including the people working on them. Ships will be cleaner, smarter, more reliable and predictable. In the end it’s all of us that benefit from cleaner air.”

There are also clear economic advantages to LNG that makes its adoption by shipping more likely. The cost of maritime bunker fuel is higher than the highest LNG prices, and looks set to increase as oil extraction costs rise. Comparatively, there is an abundance of gas available.

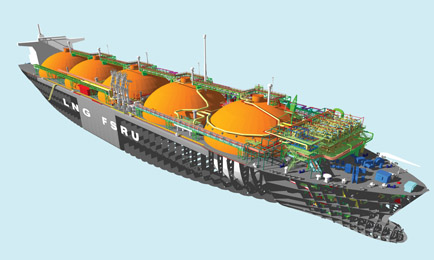

The Golar Freeze LNG Carrier was converted into a floating storage and regasification ship and is docked in Dubai

The Golar Freeze LNG Carrier was converted into a floating storage and regasification ship and is docked in Dubai

Ashworth says the shift to LNG will be “seismic” during the next ten years and likens the effect on the shipping industry to the switch from “horse and cart to motor vehicles”. However the sector has been slow to address the problem of emissions and adopt alternative technologies. He says: “Most of the shipping industry is asleep at the wheel, they don’t see that the world is changing. As the legislation bites there will be a last minute scramble to change.”

According to the ship classification society Det Norske Veritas (DNV GL) by the end of 2015 there will be 50 LNG-fuelled ships in service. Last month DNV GL recorded 100 LNG ships planned or being built around the world for the

first time. By 2020, it predicts the number to have risen to at least a thousand.

As well as changing engine technology and the design of ships, the mainstream use of LNG by shipping has will have a profound effect on LNG infrastructure. Full adoption by the maritime sector would effectively double today’s 250 million megatonne global LNG demand, says Ashworth. The technical challenges around producing, storing and using LNG were solved decades ago and that all that remains is for the technology to be further refined. The plants are scaling down the same way as mobile phones, he says. Liquefaction plants the size of shipping containers are now available, able to produce small quantities as required. Production, processing, storage and even ship refuelling facilities are also being developed that remain offshore and mobile as an economic way of producing LNG from “stranded” or small gas fields and putting into the market.

Galileo's Cryobox "nano' gas liquefaction plant, which produces LNG from natural gas is being used by ferry firms in South America

Galileo's Cryobox "nano' gas liquefaction plant, which produces LNG from natural gas is being used by ferry firms in South America

The first ports in Asia, the US and Europe are beginning to offer LNG “bunkering” to cater for the growing number of vessels that use the fuel. A survey published by Lloyd’s Register of 22 major ports last month confirmed that three quarters expected to install LNG bunkering within the next five years.

Latifat Ajala, a senior market analyst for Lloyd’s Register says: “Global ports are gearing up for a gas fuelled future for shipping. Gas can only really take off if supply is more like orthodox bunkering arrangements. Real expansion requires infrastructure and delivery capability and it is clear that ports are planning to develop that.”

For example Rotterdam, Europe’s largest port, has had a terminal for the storage and handling of liquefied natural gas since 2011. The port is working closely with Antwerp, Mannheim, Strasbourg and Switzerland Port Authorities to transfer learnings from the introduction of the LNG terminal and create a “Rhine-Main-Danube LNG corridor” with €40 million of EU subsidies. By 2020 the EU plans that all European seaports will offer LNG bunkering facilities.

The first place LNG will be used widely as a transport fuel looks set to be the maritime sector. The switch will be gradual, as new ships enter into service, but LNG is as close to a silver bullet as the shipping industry is going to get.