Our addiction to oil and gas is possibly the single most influential factor in the shaping of the modern world. Fossil fuels provide the materials that make our products, buildings, packaging for our foods and provide the energy for our homes, vehicles and gadgets. Exploration and exploitation of oil and gas resources shapes geopolitics, drives the modern environmental agenda and accelerates the advancement of technology.

But addiction to oil and gas is a two way street. Just as modern society is addicted to using oil and gas, the Middle East is addicted to producing it. For decades, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has been defined internationally by the vast wealth the region’s elite have accumulated using oil and gas. The contrast between that wealth and the terrible conflicts, hardships and cultural differences are often very stark.

But, in the last few years, the pace of societal change in the region has since massively accelerated. When street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi committed suicide in December 2010, he sparked a movement of civil unrest through the region, destabilising and reshaping countries and governments in a movement that has since been named the Arab Spring.

Despite the recent instability, the oil and gas industry has phlegmatically kept the pipelines flowing and the tankers full. Justin Dargin, a Middle East energy expert from the University of Oxford, says that people are now more aware of security issues, especially those associated with operational security. He says: “Security protocols are reviewed in the light of attacks. In Algeria, after the Amenas attack, the industry is more or less satisfied with the steps the government took afterwards.

“The oil and gas industry is robust. These companies are used to doing business with a variety of governments and characters in places other industries won’t go.”

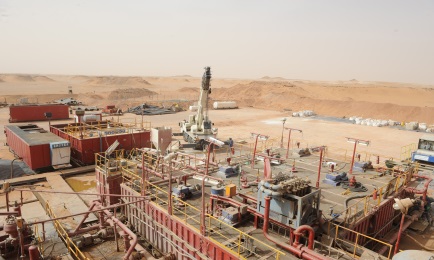

The most shocking moment for the oil and gas industry in recent times was the attack by a militant group on the In Amenas gas plant in Algeria during January 2013. The attack led to a three day siege in which 40 workers died. The gas facility is a joint venture operated by Statoil, BP and the Algerian State energy company Sonatrach. A subsequent investigation by Statoil found that the company had relied too heavily on the Algerian Army for protection. The report also made a number of recommendations to improve operational security. "The terror attack against In Amenas was unprecedented,” said Statoil investigation leader Torgeir Hagen in a statement. “It clearly demonstrates that companies like Statoil today face serious security threats."

The unprecedented attack at the In Amenas plant in Algeria this year made international headlines and prompted a review of security procedures

The unprecedented attack at the In Amenas plant in Algeria this year made international headlines and prompted a review of security procedures

The In Amenas gas plant is still operational, although planned expansion projects there and at nearby plant In Salah have been delayed. Statoil has not returned any workers to the site since the attack. BP has said that it expects to begin returning workers to the site before the end of 2013.

Another flashpoint is the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt, where Islamic militants have repeatedly targeted natural gas pipelines with bombs. According to reports there has been more than a dozen attacks in the last two years. Dargin says: “In Egypt, these militants continuously blow up pipelines in the Sinai Desert.

“But there are other issues in Egypt that will take a long time to solve. You have the political transition and the chaos, as well as crippling economic paralysis.”

Sonia Elkattan, senior trade adviser for UK Trade and Investment (UKTI) Egypt, says that there are a lot of regulations, bureaucracy and a slow court system in the country, “but all these issues are improving”.

“Despite the political instability business is going on. Democracy and liberty has a price that has to be paid. But 95% of trade remains unaffected. Egypt is still a very attractive market, especially for long term investments,” she says.

Egypt’s oil and gas sector is vital to the country, contributing 15% of its GDP. There are around 50 international exploration companies and 400 service companies working in the oil and gas sector there. The country also has nine refineries, producing 726,000 barrels a day, making it the largest refining sector in Africa.

The UK is the largest foreign investor in Egypt, representing half of all foreign money going into the country. There are more than 900 British businesses present in the country and British brands still equate with quality in the eyes of most Egyptians, says Elkattan. Most major international oil and gas companies operate there include, BP, Shell, BG Group and Eni.

Egyptian oil is mainly produced in the Western Desert, where new reserves were recently discovered that bring the country’s total oil reserves to 4.4 billion bbl. After recent natural gas discoveries, proven reserves of natural gas proven have risen to 2.2 trillion cubic metres. There is also a large amount of foreign involvement in the domestic market. A UK exploration company recently won a concession in Egypt and is investing £300m in the country, says Elkattan. The Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company, EGas, is also expected to launch a tender by the end of 2013 for a new gas exploration concession worth around £250m.

In addition there are large levels of investment in Egypt’s downstream industries. Two new refineries are being built near the Suez Canal. There is a new oil refinery and petrochemical plant is being built in Port Said. A lubricants and oil complex is being built in the Suez at a cost of £32 million. A new pipeline to transport crude oil to Alexandria is also being built, a £6 million package of work during two years.

Tahir Square in Cairo, Egypt, was a focal point for the Egyptian revolution in 2011

Tahir Square in Cairo, Egypt, was a focal point for the Egyptian revolution in 2011

Engineering firms looking to do business in Egypt should register with the government and research prospects beforehand, says Elkattan. “You have to have a presence in the market, you won’t be able to do business here by staying in the UK - and you have to be patient,” she says. “We are country with political problems, but we have 85 million people to feed and clothe. Also, Egypt will remain dependant on imports because we lack innovation and design capacity.”

The large-scale expansion of the downstream petrochemical sector in Egypt is typical across the MENA region. Unfortunately, another associated common characteristic of labour markets is a shortage of professionally skilled engineers and technicians. Laws exist in places such as Saudi Arabia to ensure that companies which employ foreign engineers and technicians also employ workers from the indigenous population. There has also been an amnesty for illegal foreign workers during the last year. Media reports suggest that the result has been that over a million foreigners have left the country in the last year. Simultaneously the Saudi government is attempting to improve the education system in the country. According to the UKTI, two new schools are currently opened every day in the country.

Justin Dargin, from the University of Oxford, says that the push to produce more skilled engineering and technical staff indicates that many MENA region governments have realised that their industries have to diversify away from just producing and exporting oil and gas in order to prosper. “Saudi Arabia, like most other MENA countries, realises that overdependence to oil export is unsustainable and volatile. That they can’t rely upon it for the long-term development of their countries,” says Dargin.

“Since the Arab Spring, there has been an expansion of the population and a rise of subsidisation across whole swathes of the economy. In order to encourage cooperation from the citizenry, there has been a massive expansion of the state and of subsidisation programmes. Because of the massive expansion, many MENA states must achieve a much higher breakeven price for their oil or they will be running deficits.”

The need to maximise the value from oil and gas in volatile international markets is a key driver in the region’s downstream boom. Saudi Arabia is home to the world’s largest oil and gas company, Aramco, and also one of the biggest chemicals processing complex to be built in one phase - the Sadara project at the Jubail Industrial City.

A joint venture with US chemicals firm Dow, the first parts of the Sadara complex are due to be commissioned in the second half of 2015. The entire complex, which is comprised of 26 processing and manufacturing units, is expected to be completed by the end of 2016. According to Saudi Aramco, the £8 billion complex will “possess flexible cracking capabilities”. It will also be able to produce “over 3 million metric tons of high value-added chemical products and performance plastics” that will also led to the setup of other downstream plants.

The Sadara complex in Saudi Arabia is expected to employ tens of thousands of workers when completed in 2016

The Sadara complex in Saudi Arabia is expected to employ tens of thousands of workers when completed in 2016

Domestic natural gas prices in MENA region countries like Saudi Arabia are heavily subsidised and cheaper than international market prices. That makes it an attractive place to set up downstream gas companies, such as chemicals and fertiliser companies.

However, the grand economic plan of diversifying around downstream oil and gas has a major blip on the horizon - North American shale gas. National oil companies (NOCs), such as Saudi Aramco, have made it widely known that the shale “revolution” does not worry them and indeed, offers them opportunities. However the long term consequences could still damage the region’s development, says Dargin.

He says: “Saudi Arabia, like most energy producing / exporting countries, is funnelling billions of dollars into the downstream petrochemical and natural gas industries. They’ve had the competitive advantage for a long time in terms of natural gas input pricing. Now that’s under threat.

“The North American shale gas revolution represents a threat to that framework of funnelling inexpensive natural gas imports to certain economic sectors. Even though they have enough natural gas reserves, it is nonassociated, which is often quite difficult to produce. Often the NOCs don’t have the expertise, technology and managerial skills to produce it. So, they have to collaborate and coordinate with international oil companies. But, the international oil companies do not want to be involved as long as the domestic price of gas is low because most, if not all, of the gas being produced is slated for domestic allocation. That is putting pressure on governments to increase the prices.”

This upward pricing pressure and the presence of shale gas on the international market means it is likely a very different pricing regime will exist in the region by the end of the decade, says Dargin.

It also means some MENA countries are pursuing the development of advanced manufacturing sectors in areas like defence, aviation and automotive, mainly through the creation of technology hubs in order to transfer know-how.

Furthermore, the region is a burgeoning market for engineers and industries of all types. Against all odds / common sense a Middle Eastern country, Qatar, is hosting Football’s World Cup in 2022. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, is host to a project to build the world’s largest public transport project. Abu Dhabi has a £56 billion budget to over the next five years to build infrastructure from airports to renewable energy projects.

The proposed stadium at Doha to be built for the 2022 World Cup

The proposed stadium at Doha to be built for the 2022 World Cup

Dargin says that the places spending the most with the greatest potential for engineers and engineering firms are Qatar, followed by the UAE and then Saudi Arabia. “These places are funnelling billions of dollars towards mega energy projects, reconfiguring their power sectors and building downstream related industries,” he says.

“The amounts of money being spent in Qatar are phenomenal. The country offers some very good opportunities for engineering firms who want long term work and remuneration packages are quite attractive”.

Dargin says governments and companies in the Middle East would be most interested in foreign engineering companies that can help them produce energy more sustainably, or reduce energy consumption more efficiently. “Any company that can position itself in that light will find that energy rich MENA countries will be very interested in what they have to say”.

However, despite noises from MENA governments heralding massive projects in renewables such as solar and hydroelectric power, the progress has been slow. Many experts believe the policy of subsidising domestic energy prices is severely hampering the development of renewable forms of energy in the region. Oil and gas remains the most important economic force in the region. “Without oil revenue, most of these megapolises would be submerged underneath the sand,” says Dargin.

“The region is very uneven in terms of development, cultural attitudes, and in adaptability. But, as a whole, by the long term, perhaps by 2025, this current period of chaotic political transition and instability will subside. Even Iraq is stabilising.”

The overall trend is that the region is becoming a friendlier place to do business, says Dargin. For example, Saudi Arabia is beginning to modify its traditional attitudes towards gender. “Each country is different,” he says. “Dubai is perhaps far more hospitable for investment than certain jurisdictions in the US. You can set up a company in Dubai in several days, often, less than a week, whereas it may take longer depending on the state.”

The dynamic time the Middle East’s oil and gas sector is undergoing is a result of the great forces of societal and economic change flowing through the region. These changes are instigated by both government and non-governmental groups and by the influence of international and domestic markets. If the world is addicted to oil, the MENA region is getting high off its own supply and mirroring the ambitions and aspirations of those it has been supplying for decades.