Articles

Since the earliest automobile, racing has been used by the motor industry as a way of testing new technical developments. Before 1906 events were not held on purpose-built tracks, but on open roads, and some of these were long races between European cities. The last city-to-city event was the Paris-to-Madrid race in May 1903. But the first stage ended in disaster, and the race was terminated early.

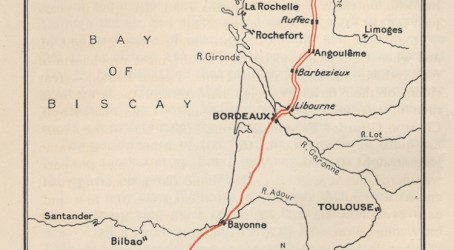

The French Prime Minister had been against the idea of the race, but the president of the Automobile Club de France, with the support of carmakers, managed to overcome opposition. The event was to cover more than 812 miles, and was to be run over three stages: Versailles to Bordeaux, Bordeaux to Vitoria and Vitoria to Madrid. There was a class for motorcycles and three classes for cars. A total of 224 vehicles started the race in Versailles.

To prevent the construction of heavy and unwieldy cars, the automobile club decided to restrict vehicle weight to 1,000kg. By that time some engines had increased in size to 90 nominal hp, with one design at 110hp.

To accommodate these heavier machines, engineers developed pressed-steel frames to which the engines were bolted. Previously engines had been carried on secondary frames. They also developed hollow axles and shafts, and increased engine efficiency

by introducing new carburettors and valves.

The race organisers intended to keep the course free from traffic. With every dangerous point marked out, it was hoped that vehicles would be able to accomplish the first stage at 60mph without risk.

As it turned out, the course was not free of traffic – spectators crowded into the road, dangers were not always signalled, and the race was badly organised. The speed was also much greater than had been anticipated. At one point a competitor was clocked achieving 90mph. No one had expected the drivers to be so competitive and to push the new machines to their utmost power.

The Engineer reported that four competitors and at least four spectators were killed, with many more injured. Wrecked cars lined the route. Nearly half of those that started were disabled during the first stage of the race. One of the casualties was Marcel Renault, the winner of the 1902 Paris-Vienna race. He was trying to pass a competitor driving a Decauville. At a bend, he was obliged to steer wide and hit a tree. Renault fell into a coma and later died.

Châtellerault Tourand lost control when he struck a ridge that ran across the road and killed two soldiers and a spectator. Loraine Barrow tried to steer clear of a dog but then another dog got in his way and the vehicle collided with a tree. Barrow’s mechanic was killed instantly, and the driver himself later died from his injuries.

A remarkable thing about the race was the failure of the big cars. Fernand Gabriel was first to Bordeaux driving a 70hp Mors. He finished in 5 hours 13 minutes, covering the course at an average speed of 66mph. The big cars, although faster when running, failed to do as well as the lower-powered vehicles because they had more difficulty handling the road conditions.

A 15hp touring vehicle was an example of reliability over speed. This car, carrying a full load of passengers, came 42nd in a time of 9 hours 15 minutes, beating some of the most powerful racing machines over the line.

Charles Jarrott finished fourth in a 45hp De Dietrich. In his book Ten Years of Motors and Motor Racing, held in the Institution of Mechanical Engineers’ collection, he wrote: “I went back over the road after the race and I marvelled not that several had been killed, but that so many had escaped.”