The nodding donkey in the square in the Dutch town of Schoonebeek is a tip of the hat to the past, when oil flowed freely from one of the largest onshore fields in Europe. The relic from the days when Schoonebeek pumped millions of barrels of oil to the surface could have stood as a permanent reminder of shutdown: when production ceased at the site many, perhaps, thought it would never be resumed.

Instead, while there are symbols of Schoonebeek’s heritage to be found by the visitor, the site now most definitely has a future. Given that oil is a finite resource, leaving some 750 million barrels in the ground seems wasteful in the extreme. That is what would have happened at Schoonebeek were it not for Shell’s use of the latest enhanced oil recovery (EOR) technology, which means the oil giant is now pumping some of that vast untapped reserve to the surface. Over the next 25 years, it is thought Schoonebeek could yield an extra 120 million barrels.

Diederik Boersma, team leader for EOR at Shell in the Netherlands, says: “Just as a matter of good stewardship, we feel it’s our responsibility to get more out of these resources. It would be a waste to just leave that behind. Also, there is a dire energy need. When you look at potential energy gaps, we need to use new technologies to increase recovery factors from existing resources.”

This is precisely what is happening at Schoonebeek. The nodding donkeys – there were once up to 250 on the field – have been replaced by 40 modern long-stroke units and the site will produce 20,000 barrels of oil each day at its peak. Production provides employment for 1,000 people. The oilfield, an important part of the region’s economy, has been revived.

Oil under Schoonebeek was discovered in the 1940s and production commenced at the end of the Second World War. Peak production was reached in 1957 and over almost 50 years the field produced 250 million barrels. But by the 1990s the amount of oil being produced was not covering the cost of production.

The oilfield’s operator, Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij (NAM) – a joint venture between Shell and ExxonMobil – took the decision to shut it down. Those hundreds of millions of barrels of oil that remained in the ground were treacly and hard to extract. Only a rise in the oil price and new technology would enable production to be restarted.

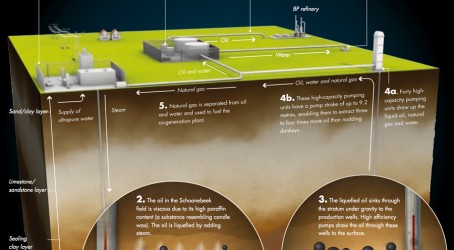

In 2007 NAM and its partner Energie Beheer Nederland found a way they thought could allow oil production to resume. By drilling new horizontal wells in the oil-bearing layer of rock, it would be possible to inject steam into the reservoir. The steam condenses to water, releasing heat, thinning the oil – which has a consistency somewhere between olive oil and pancake syrup – so that it can move more readily to horizontal production wells. High-capacity pumps could then bring the mixture of oil and water to the surface.

It is this form of thermal EOR technology that has been used to restart production at Schoonebeek.

Boersma of Shell estimates that around the world, typically 20-30% of an oil reservoir is actually produced. So methods to extract more oil are welcome. Other methods for better management of reservoirs include injecting water and gas when the flow of oil as the result of the release of pressure caused by drilling has ceased to be effective for oil extraction.

EOR itself actually involves changing the consistency of the oil to produce results. But the oil price must be at a certain level for EOR to be economical. If the part of the field being redeveloped at Schoonebeek yields the expected level of oil, some 370 million barrels will have been produced – well over a third of the reservoir’s capacity.

EOR has great potential, Boersma points out: “If you look at what you can do with EOR, if you can increase the recovery rate over the base gain, globally you’ll get 88 billion barrels – which is three years of production.

“If you reckon there’s about 70% left behind in a reservoir with current technologies, there’s a heck of a lot of oil, and a lot of years where we could enjoy it – if we manage to increase the recovery factor.”

Schoonebeek.pdf

Enhanced oil recovery delivers results

Petroleum engineers have been arguing about the possible benefits of EOR for a long time. Targets as high as producing 70% of a reservoir have been mooted. Shell has a long legacy of developing EOR techniques and was experimenting with steam as far back as the 1930s. Aside from the thermal EOR system being used at Schoonebeek, other technologies include gas injection – using CO2, natural gas or nitrogen – chemical injection and microbial injection.

Diederik Boersma of Shell says: “With the maturing of various EOR techniques you can argue that you want to apply these tertiary techniques as early as possible. When you do that you increase production rates and develop reservoirs in a short timeframe. So a lifecycle approach to field development is very beneficial economically. Currently with enhanced oil recovery we are targeting 50% of the reserve space.”

He adds: “There is a shortage of easy oil. It is disappearing in all the oilfields and the newer fields we find are the result of exploration in the Arctic, or are in very deep water. They are expensive to develop, so going back to existing oilfields for EOR becomes very attractive.

“One of the uncertainties in oilfield development is finding the oil; that uncertainty is not there if you go back to existing fields. So Schoonebeek was an existing oilfield and we went back there to do EOR. Because it’s very difficult to find cheap oil.”

Redeveloped Schoonebeek oil field facts and figures

- Schoonebeek is the largest onshore oil field in North-Western Europe

- The field was discovered in 1943, production began in 1947 and ended in 1996

- Redevelopment of the Schoonebeek oil field began in January 2009

- No nodding donkeys used: 40, 15-metre tall high-efficiency pumps will be installed

- 18 new oil extraction locations

- 73 new wells

- 17 km-long new water discharge pipeline to the Province of Twente

- 15 km of field pipelines (oil/steam/gas)

- 22 km of new oil-export pipeline, of which 12 km in Germany

- Production of between 100 and 120 million barrels of oil in the next 25 years

- A cogeneration plant will supply 120-160 MW power (90% for the public electricity grid, 10% for on-site use)