We can envisage an exciting future for 3D printing. It is one where factories have changed dramatically and feature loads of printers producing parts. There is a huge range of materials now, including digital polymers that are very tough, like ABS, and also UV resistant. 3D printing is moving to low-volume production now, and specific applications.

There are things like creating injection moulds and blow moulds, as well as end-use parts. Injection moulds, for example, can now be produced with digital ABS materials with good heat resistance. The mould can be printed, where it would normally be machined. Instead you have it in hours. It will be as good for many parts as a standard machined mould: it’s made in a tough material, with good durability.

Things like automotive parts are perfect for 3D printing. That is an area where it will be used, and in aerospace it is already being used, but in quite a niche way. It is an industry that is in its early years. There is no reason why, in the future, airlines shouldn’t have a 3D printer in the hangar at an airport to replace any parts that break.

Design cycle: Bike helmets produced using Stratasys hardware

Wilfried Vancraen, chief executive, Materialise

What is the striking thing about this year’s show? It’s the amount of companies that have popped up offering new 3D printers. What keeps Materialise alive is that all of these machines need to find applications. All the successful applications for additive layer manufacturing (ALM) are those where the design process has been automated, or semi-automated, and there is a logistical chain for the application – and that is where Materialise is active.

We are linking automated designs or large groups of designers to machines in a professional way. We help them to take CAD data or data from a scan and manipulate it. Data need to be combined and healed in such a way that warpage and support structures for the final part are controlled. Support structures need to be automatically designed. This is necessary to make commercially successful applications, which is where we support the industry. Despite the attention ALM is getting, this is still quite unusual.

Stratasys and 3D Systems use Materialise software and make extensive use of its automation in their daily operations. This indicates that there is real need for it. If a company of the size of those two was capable of developing its own software that did the same thing, it would do.

TCT has had difficult years but it has a new kind of drive and is gaining momentum. We are satisfied with this year’s show and there are more visitors. For 3D printing, the money is being made in large-scale applications where market segments shift to it as a production technology. It happened with hearing aids, it is happening in the dental industry and medical devices, and for glasses – but they need solutions where they can manufacture thousands of pairs a day.

The really nice applications of 3D printing have been in the works for years – the conceptual work was initiated well before the hype. It has to be said that the current situation is not sustainable. If you have a look at how many companies have appeared over the last year, it is obvious that some of them will not survive.

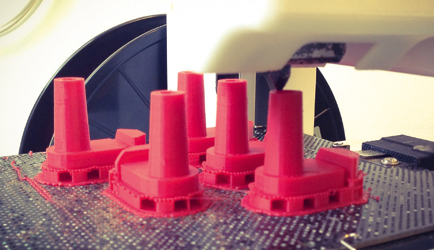

Stratasys machinery

Stephen Mellor, project engineer, Hieta Technologies

We are a start-up formed almost three years ago, backed by the Technology Strategy Board – now known as Innovate UK – with intellectual property related to design for ALM. We have built a capability in design for additive manufacturing, and we have a supply chain. We come up with new designs with a special focus on small gas turbines and Stirling engines. A lot of our work relates to CFD and stress analysis of designs, modelling both fluids and heat transfer. ALM allows more design freedom than subtractive processes, but there is not complete design freedom, as people sometimes think. For automotive and defence, where we provide engineering design services, often working on confidential research projects, the applications are about getting weight out. Hieta means ‘high efficiency’ – lighter designs.

Materials are becoming a bigger part of ALM; but you can’t pick up a book and get the information you need – people haven’t been doing it long enough. We know where ALM sits: it doesn’t replace CNC, but it has a role within manufacturing, and we’ve got the design applications that lead to business benefits. The challenge is trying to prove new designs.

The hype around 3D printing is everywhere so we’re getting more and more calls. The challenge is that people don’t always hear the bad things. Our usual discussions are a kind of reality check on what can and can’t be done. Eventually you get a part that’s suitable, but it can be a long journey.

Ultimately we will be pitching designs for high-volume manufacture of 10,000 to 50,000 units. Outside of dental, those numbers aren’t really seen anywhere.

But we need to get the process speed up. It is not equivalent to the speeds you do on a CNC machine. Our ultimate objective is to become a premium, market-leading additive manufacturing company specialising in heat management and complex lightweighting structures.

Making an exhibition: Stand clips using ALM