Articles

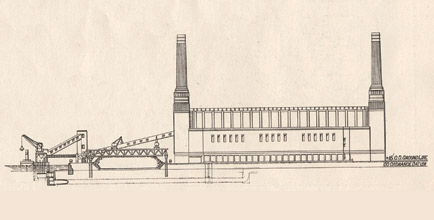

The 1930s power station had just two chimneys and was encircled by rail tracks

Battersea Power Station, with its trademark chimneys, has been an imposing figure on the London skyline for 80 years. But it has lain dormant by the banks of the Thames since October 1983. That month saw the last electricity generated by the site’s B power station. The A station had closed earlier in March 1975.

In 1980 environment secretary Michael Heseltine awarded the building grade-II listed status. This meant that demolition was no longer an option. Since then various proposals for the site’s future have been put forward – including the creation of a theme park – and later abandoned. Finally, a seven-phase redevelopment plan is now under way that will include restoration of the station’s Art Deco features. But to fully explain the importance of the site we need to look beyond its striking architecture.

In the Institution of Mechanical Engineers’ collection is a commemorative booklet celebrating the completion of Battersea A station, dated 4 June 1934 and presented by the London Power Company. At this point there existed just two chimneys. When the B station with its two further chimneys was added in the 1950s the structure would become the largest brick building in Europe.

The London Power Company’s station had replaced a localised system of electricity production and distribution dating from before the First World War. The company faced many difficulties in building the plant but the result was an engineering triumph, containing what was for 20 years the largest turbine in Europe.

Coal was delivered daily by six steamers, off-loaded by cranes onto conveyor belts and then stored in the coal house or transferred to the boiler house. The conveyor belts alone were a small but significant engineering triumph – they ran forwards and backwards, thereby maximising efficiency, and conveyed 240-400 tons of coal an hour.

Bankside delivery: Coal reached the power station by river steamer

Bankside delivery: Coal reached the power station by river steamer

The whole site was encircled by rail tracks “serving for the effective marshalling of full and empty coal trucks for ash removal” and for the delivery of goods to the turbine hall and workshop store. The site’s success was largely down to these different elements coming together to create a fully integrated delivery process: the lifeblood of 243MW of power production.

Thousands of workers were employed to build and run the station’s mechanical heart. The turbine hall housed three cylinder turbines. Each had its own feed-water heaters, evaporators and pumps. The turbines ran 24 hours a day. They were so big that they had to be transported from Manchester to Battersea in sections, set up in position and fitted together in situ. Therefore, they had not been fully tested before installation. Instead, technicians were relied on to craft the gears and parts with minute accuracy and precision.

The hall itself ran 475ft long and 80ft wide, with a glass roof rising to an apex 100ft above. Down either side of the hall were long rows of fluted columns faced with marbled tiles. The walls were faced with the same tiles, made to resemble blocks of masonry. The floors were made from oil-proofed compressed mosaic. Handrails were of specially processed steel, designed to retain lustre and provide natural light.

The famous buff chimneys reached a height of 337ft 6in. Each chimney, if put on its side, would be large enough to serve as a Tube station: each is 28ft in diameter at the inside of the base, tapering to 22ft at the top. So a platform could be built, a train could run through, and passengers would find a station loftier than normal.

The London Power Company’s own plaque, dated 23 April 1931, summarises its achievement: “On St George’s Day in the year of the centenary of Michael Faraday’s great discovery this stone of commemoration… was placed as a landmark in the development of Larger London’s light and power and to serve as another memorial of the scientific heritage derived from famous Englishmen”.

The lasting appeal of Battersea Power Station is its combination of the mechanical alongside the design – a symbiosis of machinery and architecture.