Whittle had to fight to get his ideas accepted

The Archive article about Sir Frank Whittle did little justice to the monumental battle that he had to fight, on a technological and personal level, to demonstrate the practicality of his turbine concept (PE November).

Reference was made to an engine “built by the British Thomson-Houston company,” implying a harmonious relationship which in fact was far from the case. The senior engineering management in particular could not, or did not wish to, understand Whittle’s new mathematical concepts on which his gas turbine blades were designed, a subject discussed in Whittle’s 1953 autobiography.

There was intense resentment that this young RAF upstart should question the time-honoured conventions used throughout the steam turbine industry about the way that turbine blades should be designed, resulting in Whittle’s first disappointing tests when predicted thrust was not achieved.

It was only after Whittle realised that British Thomson-Houston had made the blades to a steam turbine profile instead of to his own radical profile (doubling the angle of twist) that predicted results were obtained and serious backing became possible.

Many other frustrations were encountered but few had the vision to support Whittle’s work with anything like the enthusiasm and urgency that it deserved. One exception was S A Couling, engineering manager of the turbine gear factory, who designed the exceptionally high-speed gearing needed for getting the rotor up to ignition speed.

That Whittle suffered ill-health during the development process, but still persisted against all the odds to achieve his vision, adds yet another dimension to the achievements of one of the greatest minds of our age.

A K L McCrone, Dursley, Gloucestershire

Bigger isn’t better

Your Editor’s comment suggested a different perspective as regards the prospective large conventional nuclear plant like Hinkley Point C (PE November). It’s certainly not before time.

For prospective projects like Hinkley Point C it is easy for the engineering fraternity to slide out of any responsibility, particularly as regards cost, time and complexity. So intent are reactor engineers to build something that they will agree to anything, as if to prove technical virility. There isn’t such a line as “No, we should not build that”.

It is suspected that Hinkley Point C, like its soulmates in France and Finland, will suffer from “complexity” where systems/hierarchy are neither completely understood nor explainable. Pushed by scientists, technologists, economists and politicians, engineers delude themselves that they will eventually know what is initially unknown and is costly to find out before the build. Engineering cannot progress reasonably like this.

In the UK, large reactors could well be consigned to the past. Increasing size, higher overall thermal efficiency and relative remoteness were the aims of the former national generating boards and nuclear authorities. But it is difficult – theoretically – to see why now.

As our editor pointed out, Hinkley Point C is over-complicated, over-priced and overdue. But it is more; it could get worse. It is now tending towards complexity (not completely understandable and explainable), extortionately expensive and a decade delayed.

It may well eventually work; but Hinkley Point C could become the “carbuncle” of nuclear engineering. The process ought not to be so esoteric. Complexity is not a virtue but a vice.

William J Ralph, Woodstock, Oxfordshire

Still a future for coal

I follow the continuing debate in PE about power generation policy with interest.

Today our lives become more and more dependent on a continuous and guaranteed power supply for virtually every aspect of existence.

Other people’s concerns have been eloquently expressed about the shortcomings of windfarms, tidal generation, and power from waste disposal, but to little or no effect with the policy makers. When the potential generating capacity of these is set against the generating capability of four 500MW continuously operating baseload power stations, they are, to coin a phrase, “blowing in the wind”.

Designs exist for 900MW boiler sets employing tangential corner firing systems with NOx reduction, commissioned by the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB), but, with privatisation, mothballed. Furthermore, with the freedom to supply natural gas on a continuous basis for power generation, we have depleted much of our North Sea reserves.

Since the demise of the CEGB, we have had endless procrastination, such that our margin of surplus capacity in the grid network has dwindled to such an extent that special measures could be imminent.

Great Britain has always been able to demonstrate its natural ability for inventive genius. Surely, one of the ways forward now would be to resurrect these 900MW designs, use our vast indigenous coal supplies and invest in the development of new technology for remote coal extraction, environmentally-friendly furnace combustion or gasification, flue gas desulphurisation and carbon capture. That would allow the UK to avoid its dependence on foreign supplies in an increasingly volatile world.

With countries such as China and India continuing to build many coal-fired power stations to support their developing economies, there could be potential to sell these new technologies elsewhere.

Harvey Holmes, Hilton, Derbyshire

Pitfalls of privatisation

Your Soundbites on closing all coal-fired power stations all make good points (PE December). But only Richard Goodfellow fully hit the nail on the head when he said “There doesn’t seem any willingness to build anything at the moment”. This fact makes all other debate a waste of time.

So why will companies not build any significant power stations? The first reason is that there is no money in it. Energy is relatively cheap, such that profits cannot be made to invest in plant.

Living on sadly rundown Teesside I pay £106 per month for all my electricity and gas. I pay £270 per month council tax. That ratio does not feel right, yet the energy firms are pilloried for profiteering.

For the root cause we must go back to privatisation. This was based on the myth that the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) must be broken up to encourage competition. I discussed this at length with my then MP John Major in 1987. He had no conception of what power generation investment cost or how the system worked, but he “knew” (because Cecil Parkinson had told him) that competition slashes costs and must be forced. I said this issue was too big and important to be left to competition, and that nobody would build a big power station without a guaranteed market and price.

Who would spend £3 billion, as it was then, on something that would take 10 years to build only to find they could not generate because somebody else came in a bit cheaper?

I may be a sentimental old “Hindsight Engineer” but I am more than ever convinced that the CEGB model of an integrated technically excellent generator, with a varied portfolio of plant running on a merit order for lowest cost, cannot be beaten.

We are all going to suffer because ignorant politicians thought that they knew better.

Colin Warburton, Yarm, Stockton-on-Tees

Kirkaldy’s legacy lives on

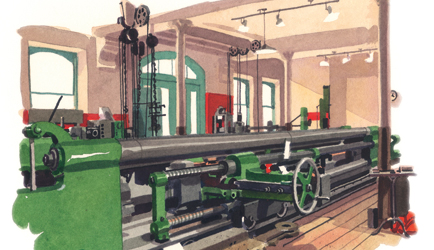

Thanks to Lee Hibbert for featuring David Kirkaldy and his massive testing machine, through thick and thin still workable in its original Southwark home (Back page, PE December).

As Hibbert says, the site has been vulnerable to development, and so it’s good to see from the website that as of 28 November the museum has a lease giving them security to 2024.

Kirkaldy was determined that “facts not opinions” should provide the basis for the materials strength data needed for design. He was a founding father of quality assurance, particularly for the new, better-value steels then becoming available.

From 1865 to 1965, father, son, daughter-in-law and grandson pursued rigorous, objective and independent testing, and the definition of standards, all typical of what we engineers rely on daily.

I do suggest that members should visit this museum – they will be in for a treat. It’s only a short walk away from London Waterloo station.

Chris Begg, Leamington Spa

Too risky to delay action

In reply to John Sharp’s letter on climate change, yes it important to get to the truth, however at some point it is necessary to accept the consensus and start acting (PE November).

We, as engineers, are guided by science. We use science every day in formulas, design criteria, etc. If we questioned every generally accepted scientific principal we would never get anything done. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change view is a consensus and is generally accepted amongst respected scientists. Is it then professional to dispute their conclusions?

Sharp also ignores a further point that should be familiar to any professional engineer, and that is risk. In other words, the probability of an undesirable consequence happening. Given time, the full consequences of human-induced climate change are second only to that of all-out nuclear war yet it could be argued that the risks are pretty close to 100%. The scientific debate is not so much about what will happen but when. Even a 2% risk of such devastating consequences would warrant urgent actions.

Iain Siekman, Hamilton, Lanarkshire

Education beats quotas

I read with astonishment the suggestion that quotas should be set to ensure that a greater proportion of engineers are women (“The last resort,” PE November). In a country that is desperately short of professional engineers and technical people, the last thing that is needed to fill the gap is a quota system which can only reduce the total number of people entering the profession. What purpose is served by striving for a gender balance?

If more people of both sexes are to be attracted to the profession what is needed is an active campaign to educate young people in what the profession is, and what rewards it can offer.

Obviously the institution is making great efforts in this direction, but this should not be limited to working through the education system. Government and the media should be pressed to stop the misuse of the term engineer to describe anyone who picks up a spanner.

R Bullen, Chepstow, Monmouthshire

Nuclear complexity

The article “Handle with care” illustrated how readily a radioactive waste disposal system becomes a complicated multidisciplinary project (PE December).

Some years ago I received an urgent request to attend the Sellafield site (then operated by a different company) to advise on the non-operability of a recently acquired asset which, like the equipment described in the article, was intended to operate with minimum maintenance in an enclosed shielded environment to dispose of radioactive waste material. The machine was failing its commissioning tests. A desk study and a visual examination revealed flaws in its concept together with a lack of attention to detail design.

Another fellow of the institution had been engaged to advise the design contractor and when we happened to meet up after the case was closed we found that we had both offered similar advice. In non-technical terms, this was “Call the scrap merchant and settle out of court”.

The intense project development work of Halliwell and Quinn for their 30-year maintenance-free radioactive swarf handling system, talked about in the piece, is to be applauded. May they have a successful outcome.

Brian Hewlett, Middlesbrough

Bread-and-butter work

For years the status of an engineer working in the UK has been the subject of many PE readers’ letters. This struck me when I was given a business card from a local man who was advertising himself as “sandwich engineer”. Yes, someone who makes sandwiches. I don’t believe the IMechE would offer such membership!

Peter Davies, Frome, Somerset