If the politicians could have their way, this country would be innovating its way out of the economic doldrums. People who have been made redundant during the recession would be knocking on the doors of investors with ground-breaking technology that will solve the problems posed by the energy crisis and climate change all in one.

Banks would be falling over themselves to fund a vast array of small businesses that would mop up the thousands of jobless young people and harness their potential to create entire new industries.

But, let’s face it, starting any business, let alone one that involves capital-intensive activities such as manufacturing, is full of pitfalls at the best of times, let alone in the aftermath of a double-dip recession. Yet there are companies innovating their way to success up and down the country. This shows that, with the right technology and financial support, it is possible for an idea to thrive, grow and develop into a world leader.

Mike Lynch is the founder of one of Britain’s most successful software companies, Autonomy. Lynch grew the company from start-up to FTSE 100 listing in 12 years and in 2011 sold the business to Hewlett-Packard for $10.3 billion. He now runs Invoke Capital, an investment company that specialises in early-stage science, technology and engineering businesses.

He says experience shows that it is possible for entrepreneurs to develop ideas into world-leading companies in the UK. He adds: “If people know that they can hit the ball out of the park occasionally there is a great driver for early-stage investment. The art is trying to work out where the leverage points are.”

He says he thinks of the process as a pipeline, with entrepreneurs starting businesses feeding in at one end and world-leading companies coming out at the other.

“The issue is that certain parts of the pipe are narrow and that is what is constraining what is going on,” he explains. These particular areas include the transition of people starting out in setting up a business, specific parts of the funding cycle, and even the functioning of capital markets.

With start-ups requiring injections of cash from investors at regular intervals there is a danger that entrepreneurs get focused on the next round of funding rather than on sales and marketing.

Early-stage “angel” investors can effectively get wiped out by subsequent rounds of investment, which can have a negative effect on angels getting on board in the first place.

“Getting a more homogeneous path through the financing would work a lot better to get those companies going,” he says.

Lynch adds that one of the biggest issues is that people with technology generally do not have access to people who do business and marketing. Controversially, Lynch also thinks that some British businesses lack ambition by not looking internationally or thinking about how to own the specific business space.

Before launching Autonomy, Lynch was an academic at the University of Cambridge. He says that, back in the 1990s when he started Autonomy, universities had the attitude that business was not the sort of work they should be doing. “This has changed now and universities realise that it is important where appropriate to have an impact, and that often means going for a company,” he explains. But there are still cultural issues that mean academics question whether they want to start firms, he adds.

Lynch says that the UK has an “amazing natural resource” in the output of universities. “But what we are not doing is converting that into economic impact sufficiently. It’s a bit like being a country that has amazing oil reserves and doesn’t have anything to dig them out.”

Intelligent Textiles is one company that has spun out of a university. Ten years ago a weaver and a lecturer from Brunel University worked together on a project to develop a wearable voice communicator for someone with cerebral palsy. In doing so they developed a method of weaving electronics into fabric using conductive yarns. At that time there was no mechanism in place to help the pair spin out the technology and create a company.

Asha Peta Thompson, director and co-founder of the company, says: “We had a fantastic technology that could go into any market. The problem was really on focus. Our company has really only got direction and focus since we got market pull rather than technology push.” This market pull came from the military seven years ago and it has taken the company where it is today, she explains. The pair have made forays into other markets, including an iPod controller, ski jackets and heating products, but they are now working with the UK, US and Canadian military.

They are working to develop a back plane that can distribute power and data through the fabric of a garment and allow soldiers to plug and play different pieces of kit without the need for a battery pack.

The company is now poised to take a slice of the £850 billion market in soldier systems. But the journey has not been easy. Thompson says: “I have learnt lessons from industry that I don’t think I could have been taught.”

The Ministry of Defence encouraged Intelligent Textiles to work with a larger company to help develop the technology. But once the project was over the big company was not interested in helping any further.

Thompson says: “I get cross with big companies because they could really be helping some of the younger companies in a much more productive way when spending their research and development pounds. Let’s stop wasting money on searching for pots of funding and support technology in smaller companies.”

Tom Hockaday is managing director of Isis Innovation, a company owned by Oxford University that helps to commercialise ideas that come out of the institution. He says that universities across the country are doing well at encouraging the commercialisation of ideas. They have “improved massively,” he adds.

But these businesses represent a small part of the economy. “It’s important but it’s not the be all and end all. I would rather see an awful lot of focus put on how you can turn a small business into a big one.”

He says that in early-stage technology companies, it can be difficult for the focus of the business to switch from the technology to the market: “They are being set up by techie people so they are really interested in perfecting the technology. But the sooner that people start thinking about customers and markets the better.”

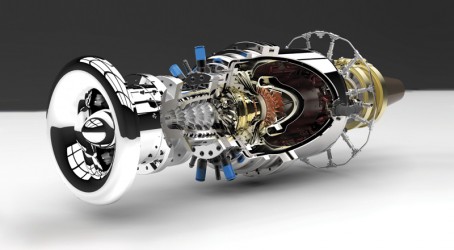

Bladon Jets is a pre-revenue generating engineering company that has got its sights firmly set on the automotive market. The company’s breakthrough micro gas turbine jet engine has potential applications in electric vehicles.

The technology was developed by brothers Paul and Chris Bladon, who had previously worked on motorbike engine development for Honda and Yamaha. A motorbike accident in the 1980s left Paul Bladon in hospital for six weeks and while laid up in bed he took his hand to developing a micro gas turbine engine.

Stumped on one aspect of the design, he asked Rolls-Royce for help. The company told him that the design would never work because it was impossible to make the one-piece compressor blade disc that was necessary.

Undeterred, the brothers spent the next three years working out how to make the part.

They went on to solve the problem, and successfully build and test a micro jet engine. But it was years later in 2008, when a fellow motorbike racer spotted the engine sitting on the mantelpiece, that the brothers set about commercialising the technology.

By 2010 the company was approached by Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) which was on the hunt for technology that could replace a conventional piston engine. Together Bladon Jets and JLR created an electric supercar concept vehicle with two gas-turbine range extenders.

JLR’s parent company took a 20% stake in Bladon Jets to give an injection of funds. Philip Lelliott, director of Bladon Jets, says that since then they have had interest from every major automotive company in the world. He says it is important to manage expectations when working with large companies that have an interest in early-stage technology.

He adds that when car companies came to visit the company to find out more about the technology, they would typically bring up to 10 people. “They have 96 million questions and expect you to go away for three weeks and answer them all.” In the early days of a business that is focused on developing a new technology, there is often not the time to address these needs.

He adds: “You need to clearly explain that you are not going to put one of these in a vehicle next year. Once you have set that stall out, things steady down and the relationship works out quite well.”

For Lelliott, one of the biggest challenges facing a technology start-up is the fact that everything takes longer than originally planned. “It always takes twice as long as you think, so from a funding point of view you need twice as much money,” he says.

He adds: “You need serious money behind you to make sure you can take your vision through to a revenue-generating point. You need specialists to help finance companies that are pre-revenue. It is quite a challenge to find investors.”

Bladon Jets secured funding from the Technology Strategy Board as part of a competition to do development work for low-carbon vehicles. This support helped to make the company attractive to investors as it footed half the costs of certain programmes.

Mentors for small firms

A new resource from the Royal Academy of Engineering is designed to put entrepreneurs who are nurturing young technology businesses in closer contact with potential investors. The Enterprise Hub draws on the skills of fellows of the academy who have experience in business to mentor start-up companies and small businesses that are trying to expand.

Ian Shott, chair of the enterprise committee at the academy, says: “Our vision for the hub is to seed a culture of success amongst the most ambitious and high-potential technology-intensive small and medium-sized enterprises.”

The hub will build clusters of expertise that can offer start-ups access to finance and routes to market. It will also work with policy makers to improve the climate for entrepreneurism and growth.

Commenting on the development, Ben Southworth, deputy chief executive of London’s Tech City investment organisation, says: “It is important that it doesn’t become locked into an institutional mindset, and that it is allowed to exist beyond these walls and is permeable.”

He believes that the key to encouraging entrepreneurism in the technology sector is to talk more intelligently about how business works. People need to think of it as something for themselves, not somebody else, he adds.