The coming together of 80 British firms at the headquarters of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers last month represented the first jockeying for position for contracts in an emerging industry that could be worth many billions of pounds.

The assembled companies included mining equipment makers, offshore engineering specialists and developers of remotely operated vehicles. They went to One Birdcage Walk to promote their wares to UK Seabed Resources, a recently established firm that has received a licence from the International Seabed Authority to harvest mineral-rich polymetallic nodules from the floor of the Pacific Ocean.

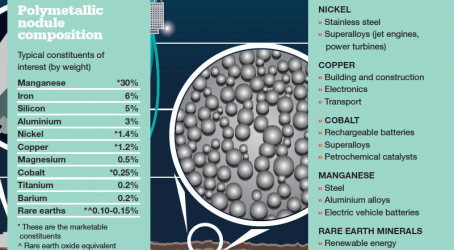

These tennis ball-sized nodules, found 4km beneath the ocean’s surface, can provide millions of tonnes of copper, nickel, cobalt and manganese, as well as rare earth minerals, which are used in the construction, aerospace, alternative energy and communications industries, among others.

UK Seabed Resources says that the harvesting of the polymetallic nodules could potentially contribute £40 billion to the national economy over a 30-year period. And it wants to tap into the expertise that British firms have gained in the North Sea oil and gas industry to help it bring the nodules to the surface.

“The world needs metals such as nickel, copper and cobalt,” says Ralph Spickermann, chief engineer at UK Seabed Resources. “And as it happens these metals are contained in handy-sized packages, on top of layers of sediment, meaning that they can be easily picked up, and pumped to the surface.”

He says the task does not involve mining, as such. “I don’t view it as mining, because it is not – it’s more of a materials handling job. But it’s a real opportunity. And we want to draw on the tremendous expertise of British firms in the offshore sector.”

Given the depth at which polymetallic nodules are found and the challenges of working several kilometres beneath the surface, it has previously been uneconomic to collect them from the ocean floor. Today, this dynamic has changed because of the development of technologies for working in space, and autonomous air and underwater vehicles used by the offshore oil industry.

UK Seabed Resources says nodules can be brought to the surface from a depth of 4,000m, using a combination of remotely operated underwater vehicles, pumps, and suction and riser pipes.

The licence that the company has been allocated covers a 58,000km2 region on the eastern edge of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, between Hawaii and Mexico. This area is thought to be particularly rich in polymetallic nodule accumulations – Spickermann claims the average density is 10kg/m2.

Exactly how the nodules might be harvested was one of the main considerations at the supplier workshop at IMechE headquarters. Specific details have yet to emerge – but Spickermann has his own ideas about requirements.

“We will need some form of proprietary machinery that can collect the mega-tonnes we need,” he says. That machinery might be a type of agricultural-type rake harvester, which mechanically disturbs the sediment.

“But it will need to have a light footprint, with some form of advanced buoyancy technology, as you do not want to be sitting on the seabed, nor using it for locomotion. The exact configuration isn’t known – but these are the sorts of technologies that I can see being developed,” he says.

Collection is just the first stage of the process, says Spickermann. Once the nodules have been harvested, they could be ground in situ to a constant consistency so that it would be easier for the riser to take them to the surface. The nodules will be relatively soft, but the slurry make-up might change as the nodules break on the way up. “So do you pump them to the surface directly or do you use some form of air lift?” he asks.

Then when the nodules have reached the containment ship on the surface, they will need some form of processing and treatment. After that comes the tricky part of loading them on to transport vessels for carriage to shore, as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone is well out of helicopter range. “These are just some of the technical issues that initially come to mind,” says Spickermann.

Aside from technology, another huge challenge that UK Seabed Resources will have to overcome is that of environmental objections. Seabed harvesting of mineral deposits does not sit comfortably with pressure groups such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth. While the seabed in the licensed area is thought to be relatively featureless at depths of 4km, there will inevitably be a degree of impact on marine biology.

Nevertheless, Spickermann insists that seabed harvesting is an “ecologically sound” method for meeting the growing global demand for precious metals, especially when compared with other techniques. “Humanity needs these metals for construction and urbanisation, so we have to make choices,” he says.

“The deep seabed covers half of the earth’s surface, and this claim is less than a tenth of 1%, and of that we will be looking at only a fraction. So this is a fraction of a fraction.”

He says that other methods of accessing valuable deposits, such as lateritic nickel ore, involve hydro-metallurgical processes and the leaching of large amounts of water through sensitive areas such as rainforests.

Potentially, the licence awarded to UK Seabed Resources could produce very large amounts of nodules, says Spickermann. “As a percentage of the known nickel reserves, this claim accounts for 12% of what’s out there. That’s a significant fraction of the world’s reserves for this mineral. It’s a real opportunity.”

In terms of safety, he says that harvesting polymetallic nodules carries far fewer risks than offshore oil and gas production. “The worst accident we can conceive of is the loss of a ship,” he says. “There’s no open wellhead. If there’s an issue, you just turn off the power.”

Looking to the future, it appears that UK Seabed Resources has already won the support of some political heavyweights. Prime Minister David Cameron attended the launch of the firm last month, where he claimed that the award of the exploration licence was “excellent news” for British companies and scientists.

Cameron said: “The UK is leading the way in this exciting new industry which has the potential to create specialist and supply chain jobs across the country and is expected to be worth up to £40 billion to the economy over the next 30 years. With our technology, skills, scientific and environmental expertise at the forefront, this demonstrates that the UK is open for business as we compete in the global race.”

UK Seabed Resources is a wholly owned subsidiary of Lockheed Martin UK, so it has the financial clout to back its ambitions. Stephen Ball, Lockheed Martin UK’s chief executive, has been vocal in his support of seabed harvesting activities. He claims that British companies, research institutions and academia are being offered exciting opportunities to become involved in this cutting-edge business.

“Environmentally responsible collection of polymetallic nodules presents a complex engineering challenge, but our team has the knowledge and experience necessary to help position the UK at the forefront of this emerging industry,” says Ball.

Seabed mining beyond any nation’s territorial waters is governed by the International Seabed Authority established under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. It has responsibility for overseeing all legal and environmental matters associated with the collection of particles from the ocean floor.

UK Seabed Resources has submitted an application for a second exploration licence, covering a separate geographical area, which is expected to be considered by the seabed authority in July.

Canadian firm eyes Papua New Guinea waters

It is not just British companies that are positioning themselves to exploit seabed mineral deposits. Canada’s Nautilus Minerals has been granted a mining lease for deposits at the Solwara 1 prospect, in the territorial waters of Papua New Guinea.

The Solwara 1 deposit, which sits on the seafloor at a depth of 1,600m, boasts a copper grade of 7%. At land-based copper mines, the copper grade averages 0.6%, says Nautilus. In addition, gold grades of over 20g/tonne have been recorded in some intercepts at Solwara 1 – the average grade is 6g/tonne.

The company has already explored the region. A drilling campaign using three remote-controlled seafloor production tools is planned, disaggregating the rock and collecting it from the seafloor. The material will be pumped as slurry through a steel riser pipe to a production support vessel above.

A dewatering plant on the vessel will extract the excess water, which will be returned via a pipeline to the seafloor. The mineralised material will be loaded on to barges for transfer to a shore-based stockpile.

The mineralised material will then be shipped to treatment facilities in China for concentrating and smelting. Nautilus expects to be taking to shore

1.3 million tonnes of material per year from the Solwara 1 deposit.

Last April Nautilus secured its first customer for the product extracted from Solwara 1, Chinese copper smelting company Tongling Nonferrous Metals Group.

In total, Nautilus also holds more than 500,000km2 of exploration territory, or tenement applications, in Papua New Guinea, Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, New Zealand and the Central Pacific.

Last September, Nautilus’s 100%-owned subsidiary, Tonga Offshore Mining, released a maiden mineral resource estimate for its Clarion-Clipperton fracture zone polymetallic nodule project, located within the Central Pacific Ocean. As with UK Seabed Resources, it wants to exploit significant grades of manganese, nickel, copper and cobalt.

Green lobby questions safety

Environmental group Friends of the Earth has raised concerns in the wake of the Pacific Ocean licence award to UK Seabed Resources.

Senior campaigner Paul de Zylva says: “Current dredging of our oceans is damaging to marine life and ecosystems. It’s a big claim to make that deep-sea mining will be squeaky clean. Can mining companies be trusted to make sure proper safeguards are in place to protect the sea and all who depend on it?

“With supplies of many minerals and metals dwindling, manufacturers should be reducing demand in the first place, by redesigning products and systems to more efficiently re-use metals already extracted.”