In a picturesque part of the North York Moors National Park, exploration drilling has been taking place in advance of plans to mine what are thought to be the world’s largest and highest-grade resources of polyhalite, a vital constituent of fertiliser. You might think that such activity would cause a furore in such a beautiful part of the world. But the project has won a lot of local support thanks to stringent efforts to minimise the environmental impact.

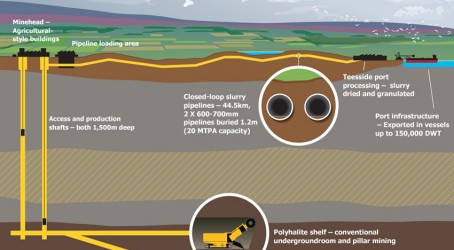

For example, all exploration sites have been returned to their original condition. Support buildings will be located in an existing commercial forestry block and completely hidden from public view, with the mine-head sunken below ground. The polyhalite will be transported from the North York Moors National Park via a 45km underground pipeline to a processing plant in Teesside, so noisy and polluting lorry traffic will not have to trundle through the country lanes.

According to Graham Clarke, operations director of Sirius Minerals, the company behind the £1 billion plan, such carefully considered design criteria are crucial for the project to have a chance of progressing. “What we have here in this region of the east of England is the biggest discovered deposit of polyhalite in the world, by many factors,” he says.

“The first phase of this project will see five million tonnes mined per year, increasing to a capacity of 15 million tonnes per year in phase two. That is just from 5% of the area that Sirius holds the mineral rights for. So there could be hundreds of years of mineable resources.

“But in an area of such tremendous natural beauty as the North York Moors, it is essential that we do all that we can to maximise the economic and social well-being of local communities but also minimise any negative impacts. And those considerations have been at the forefront of this project along every step of the way.”

Polyhalite is a source of potassium, magnesium, sulphur and calcium, more commonly known as potash, making it an important ingredient in fertiliser, enabling farmers to maintain good crop yields. Unlike the processing of potash based on potassium chloride, polyhalite treatment creates no waste byproducts – it can simply be de-watered, dried, granulated, and then blended to create a well-balanced fertiliser that has no effect on soil pH. That makes polyhalite an extremely sought-after mineral for agricultural uses, in local and international markets such as China and India.

Exploration activity has proved that polyhalite resources beneath the North York Moors to the north of Scarborough, with seams stretching out beneath the North Sea, are of high grade and are contained in very large amounts. Clarke says: “There is another deposit of polyhalite in New Mexico that is being looked at and that has average seams 2m thick. Our average is 15m, and in some areas it is up to 25m thick. It’s on a completely different scale.”

The proposed location for the York Potash mine access and surface facilities is a farm and commercial forestry block near the village of Sneaton on the outskirts of Whitby. The proposed design shows a modern mine concealed in the landscape. Buildings would be sited within the existing woodland. And mine headframes and pipeline loading areas would be sunken into the ground and housed in agricultural-style buildings to minimise their impact.

The mining process will require the drilling of twin vertical 1,500m shafts. Conventional room and pillar mining will be used, whereby the mined material will be extracted across a horizontal plane. Mechanical cutting of the rockface using carbide-tipped drills will break the mineral into small-sized deposits which will be transported by shuttle cars to the mineshaft and hoisted to the surface in 50-tonne skips.

“It’s a conventional approach,” says Clarke. “The mineral material is strong and competent so we will have very stable mine workings.”

Once it is at the surface, the polyhalite will be crushed and put into mixing tanks with brine. It will then be pumped along a 600-700mm diameter pipeline which will be laid 1.2m from the surface. There is a 200m drop from the mine site to sea level, so there is no need for additional pumping of the slurry along the route. Once it reaches the Teesside processing facility, the slurry will be bed filtered to take away the brine. The polyhalite will then be dried and fed into a granulation plant, before being shipped by sea for export and by road and rail to UK customers.

The extracted brine will be pumped back to the mine head via a second pipeline in what Clarke describes as an unnoticeable and highly efficient, closed-loop system. “It’s not a process in the truest sense – it’s just drying and reforming for transportation,” he says.

Planning permission for the pipelines falls within the remit of the National Infrastructure Directorate at the Planning Inspectorate. Sirius says it has held extensive consultations with landowners along the route, who will be rewarded financially for granting access rights.

The pipelines will be cut and filled for most of the route, although there are several water courses, such as the River Esk, which will require directional drilling. Sirius will run a fibre-optic cable alongside the pipelines for communication between the mine and the processing plant and for leak detection.

“These are relatively short pipelines with no particularly difficult obstacles to negotiate,” says Clarke. “Installation will be a one-season job of between six to eight months from spring to autumn. Once the pipes are laid, the surface will be restored to its original state so that it is not possible to detect their presence.”

Clarke says that use of a conveyor was considered for transport purposes, but this was ruled out on environmental grounds. “A conveyor would have been inappropriate and completely unnecessary because with a bit of thought and some design engineering input it can all disappear below the surface,” he says.

“Road transport was also completely out of the question because of the volumes of mineral we are discussing and because of the area we are in, and rail the same. Pipelines as a means of transporting minerals are the safest and most efficient from an operational point of view and an economic and environmental point of view.”

Sirius has already received the required planning permissions for the offshore mining aspects of the York Potash project from the Marine Management Organisation. Planning documents have also been submitted to the North York Moors National Park Authority, and a decision on whether to grant consent is expected in July.

Sirius says that, despite concerns about the visual and environmental impacts of the project, it has received strong support from local people, with 91% of respondents to the consultation programme getting behind the proposals.

The York, North Yorkshire and East Riding Local Enterprise Partnership and the Leeds, York and North Yorkshire Chamber of Commerce have also expressed support. The regional tourism body Welcome to Yorkshire has also confirmed its support for the mine which it believes will be beneficial for the economy of the wider area.

“We believe we have a very strong planning case,” says Clarke. He says that first-stage construction could start as early as this year in preparation for the bulk of the project’s work. If all goes well, the mine could be open in 2016.

Project promises big stimulus for the Yorkshire economy

The task of presenting the social benefits of the York Potash project falls to Gareth Edmunds, head of external affairs at Sirius Minerals. It is his job to explain the positive aspects of the project to the local community and to business organisations.

Edmunds says that the mine will provide a major stimulus for the North Yorkshire economy – creating jobs, improving skills and contributing to people’s prosperity for generations to come. “The project will create more than 1,000 direct jobs, and will lead to royalty revenues for local landowners,” he says.

“This area is very rural – there are not many other job opportunities bar tourism and agriculture. We want to create jobs, help build up the skills base and then encourage young people to stay in the local area.”

Sirius says it is creating 20 engineering apprenticeships in preparation for operational roles such as mechanical fitters, electricians and multi-skilled operators. Successful candidates will complete a three-year scheme which will see them spend a year in full-time training before progressing to “on the job” training. Apprentices with potential will be encouraged to progress their careers within the company to become fully qualified engineers. Edmunds says that Sirius is also working with local schools and colleges to embed content related to the project into the curriculum.

Meanwhile, the York Potash Foundation has been set up by the company to allow the community to benefit financially from the mine. Sirius will contribute an annual royalty of 0.5% of revenue from the project to the independently run body.

The payment could be £3 million a year at phase-one production and up to £9 million at full production. Edmunds says that a start-up fund of £2 million will be contributed by the company on the commencement of construction.

The foundation will support community projects. These are expected to range from scholarships and skills training to environmental initiatives. “We want to make sure that the wider community benefits from the construction and operation of the mine,” says Edmunds.

Opposition campaigns

A controversial project such as the York Potash mine doesn’t come without objections, and social media make it easier for opposition groups to mobilise support.

Although Sirius says that its consultation programme has proved that the vast majority of local people support the proposals, a Stop the Potash Mine campaign has been launched on Twitter to “help save the North York Moors from becoming another victim of big business as it destroys the environment for profit”.

A petition page – Don’t Shaft the North York Moors – has also been established, which at the time of going to press had attracted a total of 327 signatures.