Faun Trackway

Based: Anglesey, North Wales

Product: Military track systems

Employees: 150

Turnover: £30 million

Exports: 40% of sales

Exporting is not always easy – and that has often proved to be the case for Faun Trackway. The North Wales maker of aluminium military track systems does business with most of the world’s major defence nations, and that means it has to navigate its way through a host of differing procurement policies.

“Having to deal with the different quirks of each procurement authority does make doing business harder for us,” says managing director J Alun Jones. “It adds to the time that contracts take. It is not unusual to work on contracts that take 36 months from start to finish. It adds to the frustration at times but you just have to accept that.”

Sometimes countries combine procurement activities to benefit from economies of scale, and that adds cultural differences into the blend. Jones says that Faun Trackway does its best to be conscious of differences in national psyche. It was recently involved in a joint contract to sell hydraulics-based heavy-ground track systems to the Swedish and Swiss militaries, and found that the two nations had very different ways of going about business.

“The Swiss were precise and bureaucratic, whereas the Swedes were more relaxed,” says Jones. “The Swiss wanted specification changes implemented, which the Swedes were happy to accept. The Swedes saw the bigger picture – they realised they were getting more purchasing power by combining with the Swiss, and so that value outweighed any extra cost that the additional specification brought.”

Faun Trackway tends to work with local agents, because they often have the best knowledge of local markets. But on bigger, more complex projects it prefers to sit down face-to-face with the customer to help build trust and to ensure that all technical details are correct. “There is a role for technologies such as video conferencing but sometimes mistakes can be made,” says Jones. “When you sit down with people in a room, you tend to get the complete picture.”

Faun Trackway takes a methodical approach to its exporting, setting clear plans and objectives in each geographical market. A lot of its success depends on having good sales engineers who understand the export sector. Jones says it’s not possible to take an engineer whose business model has always been based on the UK and then expect it to be replicated in a foreign market.

“You also have to make sure you have a good story to tell, and back it up with good marketing,” he says. “Make sure you have a good website – doing so costs time and money but it’s a window into your firm. And if you attend trade shows be active in inviting target customers to the stand – you cannot expect them to come to you. And follow up your leads – what’s the point in going to these shows if you don’t bother doing that?”

Company: Zeeko

Based: Coalville, Leicestershire

Product: Ultra-precision polishing machines

Employees: 34

Turnover: £6.5 million

Exports: 98% of sales

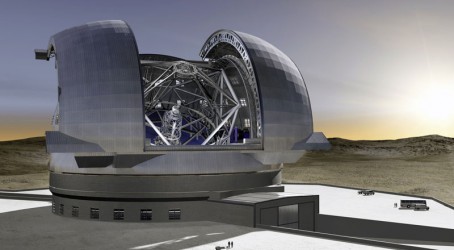

Zeeko is the classic niche-market operator. The company produces machines that are used to polish ultra-precision surfaces for telescope mirrors and other optical applications. Its narrow focus gives it a relatively low number of customers. And that suits Zeeko down to the ground.

“It’s not a limitless market, and that means everyone tends to know everyone,” says Richard Freeman, Zeeko’s managing director. “We sell into a scientific market, and there is a big element of word of mouth. We are a relatively young company, and we had to work hard to get ourselves noticed. We gave ourselves a slightly unusual name, we delivered papers at conferences, we visited international trade shows, and we networked hard. Then we built connections with universities around the world. We set out to do business in many different ways – but essentially I would call it ‘relationship marketing’.”

Zeeko’s machines can sell at £1 million each. The company is growing rapidly since it was established 10 years ago, but it still produces only between 12 and 15 machines a year. The high specification of the machines means that Zeeko avoids competing against firms with low labour costs, giving it the chance to make a decent margin. Its products have been sold in Japan, the US and in many European countries.

Freeman says cultural differences have to be respected. “The best example of that is in Japan,” he says. “We found that you have to prove you are committed to the Japanese market if you want to do business there. It was hard work – we had to leave a lot of business cards, we went to a lot of conferences, we rented out office space and put in demonstration machines. We spent three years doing such things. If you don’t show you are really committed to the Japanese market, then you haven’t got a snowball’s chance in hell of doing business there.”

Freeman predicts future export growth for Zeeko and he has his eye on the Russian market in particular. He also sees additional applications for the polishing machines that Zeeko produces. “We made machines that made telescope optics and that then developed into machines that made higher-specification X-ray telescopes. Health care is also providing some interesting applications – things branch out quickly.

“It’s a case of discovering where these new opportunities are, and that’s where our links into universities prove so valuable. We try to remain fleet-of-foot and watch closely what is going on out there.”

He admits that there is no sure-fire way to gain success in export markets. But he does think there are certain attributes that give some companies a better chance than others. “You have to keep at it, you have to play the long game,” he says. “The first thing you lose is your nerve – I’ve seen that many times before.”

WFEL

Based: Heaton Chapel, Stockport

Product: Tactical military bridges

Employees: 250

Turnover: £40 million

Exports: 95% of sales

WFEL emerged out of the Fairey Aviation Company that was founded in 1915 and was famous for building the DH9 and DH10 long-range bombers. By the 1950s it became clear that the aviation market was becoming dominated by a handful of global players, so Fairey looked to diversify into other markets.

Over time it established itself as one of the world’s leading makers of tactical bridges, which are used by the military to help advancing forces progress where retreating armies have blown-up bridges. They are also used for relief and rescue efforts following emergencies such as earthquakes and floods.

Now known as WFEL, the company excels in global markets. Its medium girder bridge has been sold in volumes of hundreds to the US military, while a follow-on order for dry support bridges could be worth a total of $600 million over a 15-year period. It’s no exaggeration to say that WFEL has become a British exporting phenomenon – so what is the secret of its success?

“We always like to do business face-to-face,” says Max Houghton, sales and marketing director. “First of all we qualify the market – it has to be a country that wants our bridges. UK Trade and Investment then provides us with a list of agents, and we whittle them down and then interview them to find the most appropriate.

“We use agents to make the initial contact and establish business opportunities. Then we do the face-to-face meeting with our own people. This works better for us because it means details don’t get lost in translation. It’s an expensive approach – but you do need deep pockets to do international business in the defence sector.”

Houghton says the key to exporting is having a good knowledge of the local market. “You have to take your UK head off and think locally,” he says. “In some parts of the world such as the Middle East, there simply isn’t the same urgency as we have over here – life is more relaxed. So you can turn up for an appointment and find yourself the only person there. But you have to accept that. You have to be prepared to do business at their speed.”

In WFEL’s sector, attending major trade shows and exhibitions is a proven route to export success. The firm attends many international events and has a presence at regional exhibitions in countries such as Brazil, Turkey and Brunei. Houghton says: “The military shows get important military delegations coming round. So they still work for us. We are there to sell.”

Houghton says that his advice for other firms thinking of exporting is to make the most of export support organisations such as UK Trade and Investment. And he says that patience is a virtue. “You have to stay committed,” he says. “We have been trying to do business in Venezuela for three years and have sent a man over there four or five times. We have nothing to show for it yet but are prepared to play the long game.”

FSG Tool and Die

Based: Llantrisant, Mid-Glamorgan

Product: Toolmaker

Employees: 85

Turnover: £6 million

Exports: 40% of sales

As a proud Welshman, Gareth Jenkins enjoys doing business in South Africa. It gives him a chance to talk about one of the biggest loves of his life – rugby.

“South Africans tend to be as mad on rugby as the Welsh,” he says. “It gives me a good way to get to know people and build relationships. That’s what business is all about.”

Jenkins is managing director of Mid-Glamorgan-based FSG Tool and Die. Founded in 1961, almost half of its business is now accounted for by exports, and it is currently selling to countries such as the US, Brazil, Indonesia, Japan, South Africa and Nigeria, and the list is growing.

Jenkins says that the success of FSG shows that it’s a myth that British firms cannot compete in international markets. “Export is gold-dust,” he says. “It is vital for a sustainable future. Small firms often find it tough because they lack resources. But it can be done. If you are not exporting, then you probably have a business weakness.”

FSG has done particularly well in South Africa and Jenkins predicts that there is a lot of business still out there. FSG prefers to deal directly with its customers, rather than through an agent, because it says face-to-face meetings tend to lead to a more technical dialogue. This has meant that the firm has had to take on an adequate number of sales engineers.

In the South African market, networking proved to be the key to winning business. “We did a major contract for a big company and it introduced us to other firms that it thought would be interested in our products and services,” he recalls. “Recommendations are priceless. You can waste a lot of time and money at exhibitions and shows. But winning new business through recommendation means you can grow your business at modest cost.”

Jenkins says that, culturally, South Africa is very similar to the UK. He says that his engineering customers aren’t bothered by superficial things like expensive suits and wearing a collar and tie – business is done on the quality of product and service. He says that the time difference is not a problem – FSG has found doing business there trouble-free.

“We use video conferencing and Skype to communicate, and we can use the internet to share technical designs which can be amended in real time. It’s a lot easier than the days of posting drawings. The world is a lot smaller now.”

Looking forward, FSG says that it has its eye on some surprising markets. “We have just sent our first shipment to Iran,” he says. “We had to go through the usual restrictions with the government, but these things can be easily overcome. It was quite straightforward really.”

Buhler Sortex

Based: East London

Product: Food processing machines

Employees: 230

Turnover: £80 million

Exports: 95% of sales

The London 2012 Olympics gave Buhler Sortex a springboard for its exporting activities. The grain and food processing equipment maker was based on a site within what is now the Olympic Park. Compulsory purchase allowed it to move to a bigger and better facility a few miles down the road, and the company has used that new start to continue its push into international markets.

The sorting equipment that Buhler Sortex produces uses high-end optical technologies to identify and remove foreign and defect materials in foods and grains such as rice, lentils, pulses and peanuts. The machines work at phenomenal speed – one of its systems can check for foreign materials at a speed of 150,000 grains of rice per second. It’s this kind of performance that has seen the firm sell its products around the world.

“Generally we use a sister company in the group located in the country of sales to handle sales/servicing and distribution,” says Nick Wilkins, manufacturing director at Buhler Sortex. “In some markets we do use agents, it depends on country size and potential. Having sales/servicing as part of the group gives us a good cultural understanding of the market. It gives us local presence and enables us to have a fast response and support.”

India is now the company’s biggest market, accounting for 20-25% of turnover. Wilkins says that the Indian market has its own characteristics that set it apart from other markets. “In India companies have high expectations in terms of service and support – the full cost of ownership is important. So we sell a lot of total-care packages. It’s popular because they like a belt-and-braces approach to anything going wrong. In the UK and Europe, there is a different attitude to risk and if anything goes wrong they are prepared to pay on top to get it sorted.”

The market in India is often seen as being highly price-sensitive. But Wilkins says that didn’t put off Buhler Sortex, which admits it doesn’t sell the cheapest food processing equipment. “Lots of companies are scared of business in emerging nations because they expect to get undercut. Indeed, we are not the cheapest, and we have a lot of low-cost competitors. But we are technology leaders and, as a result of the specification of our equipment, what we offer is value as a whole package. Some rival firms are cheap but they don’t offer value. We add value. Our customers get a better standard of food, and that means they can charge higher prices.”

Wilkins says that exporting to as many countries as Buhler Sortex does brings its own set of problems. It’s important to stay on top of the market requirements in every country. That is harder when you export to many countries. There might be different government policies, higher import duties, and access to finance might be harder to find.

As for the future, there aren’t many countries that Buhler Sortex doesn’t already export to. But it is keeping a careful eye on how its products might branch out into other sectors. “Our sorting machines could have big potential in areas such as plastics recycling,” says Wilkins.

Severn Glocon

Based: Gloucester

Product: Process control and choke valves

Employees: 240

Turnover: £52 million

Exports: 70% of sales

British engineering still has real cachet around the world. So says Colin Findlay, divisional managing director of Severn Glocon, the Gloucester-based manufacturer of process control valves for hostile environments in the oil and gas sector. Findlay finds that export customers have a high opinion of British quality and Severn Glocon actively exploits that goodwill.

“Being British still has cachet, particularly in the Middle East and in Commonwealth countries,” he says. “They like British products, they view them as being high-quality and reliable. Being a British firm often gets us the opportunity to trade.”

Many of Severn Glocon’s valves are built to bespoke specification. That enables the firm to build “engineering intelligence” into its products and therefore to position itself at the high end of the market. That enables it to differentiate itself from some of the larger, mainly US-based valve producers and to win business in markets as diverse as Australia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, China, Norway and Brazil.

“We sell a technical product and we have to show that we understand it,” says Findlay. “That means we have put people on the ground in all markets that we sell to. It’s a big investment. But having our own people means we know that we can talk to our customers in the level of depth that is required. That’s what makes us a success. It’s a very expensive way to operate, but having that localisation strategy in place is key to our success.”

Findlay says that each market differs dramatically. Saudi Arabia is renowned for being very slow-moving and contract approval can take an awfully long time. He says there is a culture of upward referral, so it can be hard to get anyone to make a decision. “But once a deal is struck, it is quite difficult and quite rare for changes to be made and the risk of order cancellation is minimal.”

Norway has a very high technical threshold when it comes to process control gear for offshore environments – even higher than the UK. So there are more technical hurdles to overcome, Findlay says, but that helps to keep low-end suppliers out of the market. In Korea, meanwhile, the business environment is very contractual, he says.

“We have even sold our products to Iran,” he says. “There are obvious difficulties in getting the required export licences – you have to make sure you are absolutely compliant.”

Brazil has emerged as a particularly strong export market, but Findlay says that it took Severn Glocon two years just to establish links to Petrobras, the national oil company. “Brazil wants local content – there is a strong drive for local jobs. We are looking at establishing a final assembly plant there to ensure we meet that requirement.”

And his advice to other firms looking to export? “You have to take the long-term view. And you have to be able to differentiate from the mass market. You have got to be different from the conglomerates who try to standardise the world.

“We have been tenacious – we went to the more challenging markets before the big boys got there. Don’t be scared, stick with it, it often takes time. Our success is the result of a 10-year plan that has enabled us to get where we are today.”