Read the latest on marine renewable energy in "Energy Islands: Orkney's radical marine power experiment is a blueprint for the future".

In 12 months, a single SR2000 floating turbine off the coast of Orkney generated over 3GWh – more than the whole Scottish wave and tidal sector managed in the 12 years up to 2016. It supplied energy for the equivalent of 830 households, weathering the worst winter storms for years in the process.

The announcement last August was a celebration for Orbital, which changed its name from Scotrenewables Tidal Power shortly afterwards in a reflection of the company’s global ambitions. There was also positive news elsewhere in the UK tidal sector – Meygen, for example, recently generated 8GWh from four tidal turbines in the Pentland Firth between Orkney and the mainland.

The sector’s success painted a picture of a rosy future for a sea-bound UK. A government-cited estimate put the country’s share of European tidal resources at 50% – and, after years of dedicated R&D, British technology existed to tap it. But there were stormy seas ahead.

Fast-flowing environment

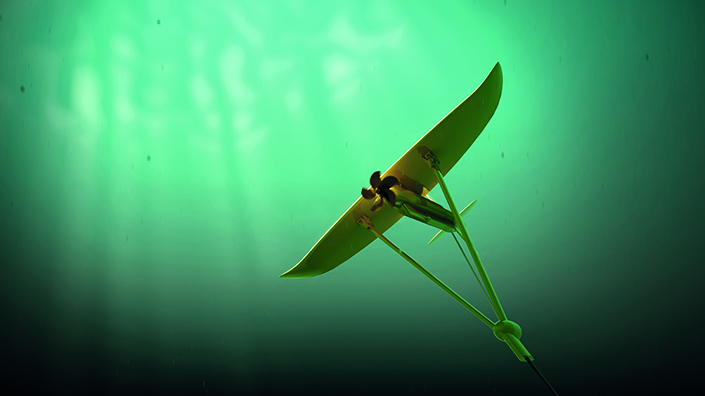

The number of technologies in development for installation in fast tidal channels reflects the vast size of the potential resource. Devices include underwater ‘kites’ from Minesto that swim in figures-of-eight to power their under-wing turbines, and vertical-axis turbines with blades pushed around a vertical pole. Other concepts highlighted by the European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC), where Orbital is based, include oscillating hydrofoils to drive hydraulic systems, and Venturi-effect devices, which concentrate tidal flow through narrow tunnels towards turbines.

The most recognisable technology is the horizontal-axis turbine, nearly identical to offshore wind turbines but smaller, with blades beneath the water. Marine engineers immediately saw an analogy with wind when creating tidal devices, says Scott.

“That familiarity – to a large degree – was taken too far,” he claims. “Most of them set about ‘marinising’ drivetrains to be installed on wind-turbine towers at the bottom of the sea. And I would argue that that betrays a very real lack of understanding of the working environment.”

That environment is one of the most challenging in which engineers operate. In depths of 30-40m, the water speed might be 16km/h, with only a few minutes of slack per day. The water’s high density and resulting increased power relative to air – an appealing aspect for energy generation – is a challenge. Installing turbine nacelles that might weigh more than 100 tonnes is no easy task, requiring huge marine construction vehicles.

Sites are also very difficult to reach. Promising tidal streams are normally found between funnelling geographical features, frequently in rocky areas around remote islands or craggy headlands. This can also make maintenance difficult and very expensive. If underwater turbines are analogous to wind turbines, Scott says, operators can expect between six and 12 maintenance interventions per year. If the operators need heavy-lifting machines to remove turbines from the seabed, they could spend more than £100,000 a day.

Enter Orbital’s SR2000. “A boat is a far better solution to be able to manufacture, install cost effectively and – crucially – access for maintenance through life, than an underwater wind turbine,” says the CEO and mechanical engineer.

'A new benchmark'? The SR2000 generated as much electricity in 12 months as Scotland's whole tidal sector in 12 years (Credit: Orbital Marine Power)

The record-breaking prototype – and its commercial successor under development, the O2 – is a UK-built floating generator with two 1MW turbines that extend from port and starboard beneath the hull once tugged into place. The tube-like body contains the drives, transformers, switchgear, oil filtration, power electronics and control systems, which work with the current to rotate the structure between facing flood and ebb tides. The SR2000 worked autonomously after just half a year of operation, with fibre-optic cables, wi-fi, radio and 4G signals allowing managers to take over using a smartphone application if needed.

Mooring lines monitor the loads on the device, and controls can reduce generation to manage loads or balance thrust between the two turbine-rotors. A dynamic electrical connection uses a wet mate connector and turret-mounted slip ring, allowing continuous exporting of electricity to the land, even when turning.

The flexibility and reliability offered by floating tidal power makes it suited for a range of installations, says Scott – single units for remote coastal communities all the way up to mega-farms with hundreds of turbines. And although many tidal pioneers are based in or have projects in the UK – Orbital, Atlantis’s Meygen, Nova Innovation, and Minesto with its kite generators – there are large potential sites off the coasts of other countries, some of which might have more amenable governments with considerable pull of their own.

‘A very unfortunate situation’

“The UK is very lucky in that we are blessed with tidal resources,” says Barnaby Wharton, head of policy at trade association Renewable UK. “It seems like a very sensible course for us to be pursuing.”

Sensible, perhaps – simple, no. “We are in a very unfortunate situation,” says Orbital’s Scott. “Ten or 15 years ago we had infrastructure, we had engineering know-how, we had supply-chain solutions – it was a jigsaw puzzle with all the pieces, we just had to put it together. I think unfortunately what has happened is that we were all maybe a little bit wet behind the ears and overly optimistic.”

Some projects failed, such as Tidal Energy’s 400kW DeltaStream project using 12m tall turbines off the coast of Pembrokeshire in Wales. The £18m installation stopped working within months thanks to a faulty sonar system and a subsequent mechanical issue.

The UK’s most high-profile tidal concept, the Swansea Lagoon, failed to progress altogether after persistent arguments and an insistent PR campaign left government ministers ambivalent and concerned about the projected £1.3bn price tag – although the lagoon technology, which would have used 16 turbines embedded in a 9km sea wall, is a “very different proposition” from multiple units in a tidal stream, says Scott (since this magazine feature went to print, Tidal Power has announced plans to go ahead with the project).

Even with small-scale projects there would always be issues, he says. “This was never going to be like the dotcom boom, where you lock half a dozen intelligent students, computer programmers, in a garage and give them a million pounds, and three years later you’ve got a billion-pound business. It is marine engineering, it’s going to cost money and it’s going to take time.”

All that time has given other technologies such as wind turbines, solar panels and biomass generators a head start, bringing prices down and delivering major change to the UK energy mix. Those steps forward have made it harder for tidal-energy companies to justify their requirements.

The Swansea Bay Tidal Lagoon project is the UK's most high-profile tidal scheme (Credit: Tidal Lagoon Power)

A recent government policy change has made it even harder – until 2016, about 100MW of energy capacity was ring-fenced for slightly more expensive but less developed sources, such as tidal or wave. That policy ended, however, and the government now only awards contracts for the lowest-cost sources.

“That really is a shame,” says Scott. “Ultimately the majority of the heavy lifting, risk-taking has been done by the private sector and done under confidence that at the end of the day there will be a commercial market.”

A spokesman for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy says: “We are absolutely committed to ensuring our renewables sector continues to thrive through our Clean Growth Strategy, and by 2021 we’ll have invested over £2.5bn in low-carbon innovations. We recognise the potential of marine technologies, and £90m has been made available to develop these since 2010.”

Any proposals, however, must demonstrate value for money for consumers and taxpayers, he adds. Tidal energy cannot yet compete with the roughly £100/MWh cost of offshore wind, let alone the projected £63/MWh for onshore wind by 2020, a bargain price that is reportedly encouraging growing political support for the long-shunned energy source.

Yet the energy mix needs to be exactly that – a mix. The wind does not always blow, so tidal energy could provide much-needed regularity in future. Decarbonising the energy system and transport requires long-term strategies, and mature tidal energy could pay dividends as the UK tries to meet its goals set in the Paris agreement and legally binding low-carbon targets under the Climate Change Act.

“Long-term strategic initiatives,” says Scott, “will require huge investments from supply-chain private-sector companies, and in that context consistency of signal from government and regulators is very, very important.”

He adds: “At this stage, before we have got capacity and learning and all those things that onshore and offshore wind have got in spades, we are simply unable to be cost-competitive against them, so effectively there is no market here for us.”

‘It will slip through our fingers’

Despite the geographical opportunities, promising companies with quickly developing technology, a rich engineering heritage from oil and gas, marine infrastructure and climate-change requirements, tidal energy has almost no market in the UK. That threatens not only a promising and reliable future energy source, but wider industrial and economic benefits from potential global dominance in manufacturing turbines.

For some in the sector, the parallels with another energy source are clear. In the 1970s, say Scott and Wharton, the UK missed a chance to take a lead in onshore wind. As a result, says Wharton, Germany and Denmark “stole the march on us”. When the first large-scale wind turbine was installed in Orkney in 1981, it came from Denmark, and by 1983 the UK was a net importer of onshore wind technology, according to a 2016 report for the Marine Alliance for Science and Technology for Scotland. “I don’t want to see that happen again in this sector,” says Wharton.

That could be exactly what happens, however, as more countries actively pursue large-scale projects. Last autumn, for example, Atlantis – the principally UK-based company behind Meygen – announced plans for the largest tidal project in Europe, a potentially 2GW array off Normandy.

Firms might also be tempted by growing tidal ambitions in Canada and elsewhere. “They are deliberately targeting this sector now because they see the UK government slipping,” claims Minesto chief executive Martin Edlund, who says the Swedish firm is “basically Welsh” thanks to its major investment in its Holyhead Deep installation. “What happened with wind is happening again. With the lack of political patience and determination, it will slip through our fingers again.”

‘You have to be optimistic’

In the raging waters of the UK energy sector, Edlund and Scott still cling to hope. They hold faith that good news stories from far-flung installations will filter through to politicians, showing a clear “line of sight” to low-cost, low-risk electricity.

“You have to be optimistic in this space,” says Scott. “If you look at the history of tidal energy over the last 10 years, a number of large-scale drivetrains have generated gigawatt hours. That is far more than in the analogous stage of wind turbines onshore back in the 1970s.”

While Westminster only wants the cheapest energy, devolved governments are more forward thinking. Minesto hopes to build a commercial tidal array with a total capacity of 80MW at Holyhead Deep thanks to the Welsh government’s commitment to marine renewable energy. Although the capacity is much smaller than that of the largest windfarm, which offers 659MW, it could be a welcome boost.

Minesto's 'kite' turbine moves in figures-of-eight as it generates electricity (Credit: Minesto)

“I’m convinced that Westminster will realise that, with hard facts on the table, they can no longer ignore the sector,” says Edlund, but the clock is ticking. “Will the timing be right for enough developers to remain in the UK?”

Some are already looking overseas – Orbital’s announcement of the SR2000’s success last year was a celebration tinged with disappointment, as Scott claims there was a “total lack” of market support. The company, he says, had “no option” but to focus the business on overseas opportunities.

So, despite the UK’s ideal geography, decades of marine engineering experience and wealth of advanced technology, new tides might sweep companies to foreign shores.

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.