That was the damning assessment of workplace stress offered by project engineering manager Matthew, in a Professional Engineering survey on mental health and wellbeing.

Sent on 9 March 2020, the survey revealed shocking levels of stress and related health issues among engineers – more than three-quarters (77.8%) said their work was often stressful, while over half (53.7%) said workplace stress had a negative effect on their mental health or wellbeing.

The UK entered lockdown just over two weeks later, uprooting long-established patterns of working and catapulting employees into an unfamiliar patchwork system of working from home, video calls and countless other adjustments. It’s taken two years for a tentative sense of normality to return.

With many aspects of work and home life returning closer to how they were pre-March 2020, we contacted readers again to see how things have changed. The responses make for grim reading.

“Been on the edge of a breakdown for 10 months now,” says one engineer. “Slowly bringing myself back from the brink. It only takes a few incidents and I’m back on the edge again.”

That precarious feeling was reported time and time again by respondents. Stress remains at crisis levels – but, among the darkness of the pandemic, there were some small glimmers of hope.

Tipping the balance

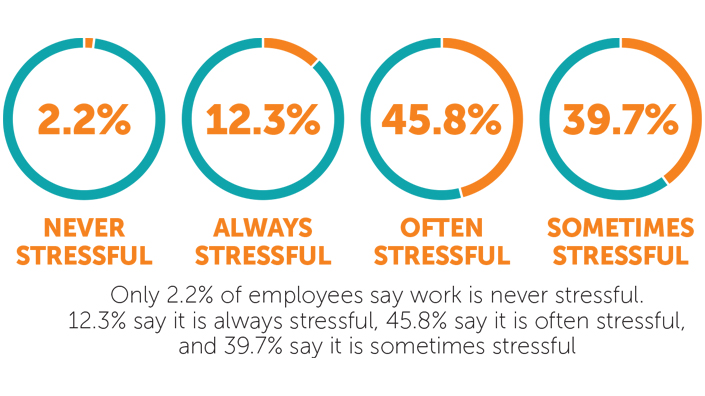

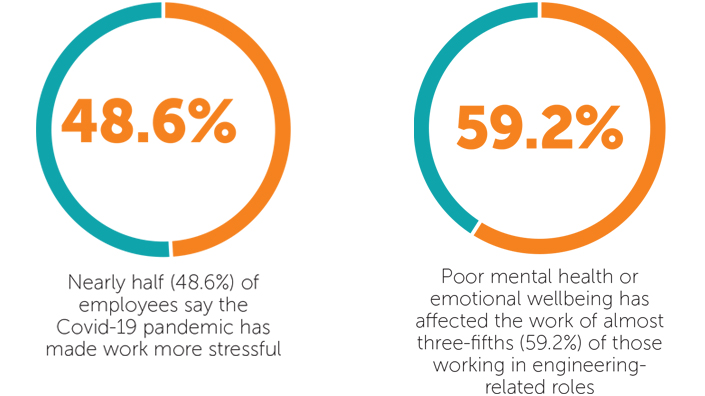

Findings from the 2022 survey of 199 people leave little room for doubt. Of the 179 respondents who are employed in an engineering-related role, nearly half (48.6%) say Covid-19 has made work more stressful. Only 2.2% of employees say work is never stressful – far less than the worrying 12.3% who say it is always stressful.

For some, the increased independence of working during the pandemic was a blessing. For others, it had countless negatives – difficulties balancing family life and work, emails and meetings bleeding into free time, less spontaneous problem-solving with colleagues, and bigger workloads as team-mates went off sick. Even things as mundane as slow broadband suddenly became significant hurdles to efficient work, with knock-on effects to stress and mental health.

“Hybrid working landed instantly, and with it greater connectivity and the blurring of boundaries between home and personal life,” says one engineering manager. “The use of platforms like Microsoft Teams has connected us, and has also led to everyone being available by instant message to everyone, all of the time… Multi-tasking for more than nine hours a day, five days a week is tiring.”

That experience would likely sound familiar to millions of people working across many different professions, but the nature of engineering work itself brought some unique challenges. Hybrid and virtual work caused delays and spending increases to hands-on projects, while key markets such as aviation slowed down, and supply-chain disruption – exacerbated by Brexit – caused havoc.

Working during the pandemic meant “fewer resources, both material and human,” says respondent Paul. This led to “constant firefighting” as the team struggled to keep production going with seemingly endless shortages. “It’s exhausting being constantly at a high level of anxiety and stress, with little to no sign that it’s going to get better soon,” he adds.

Vicious cycle

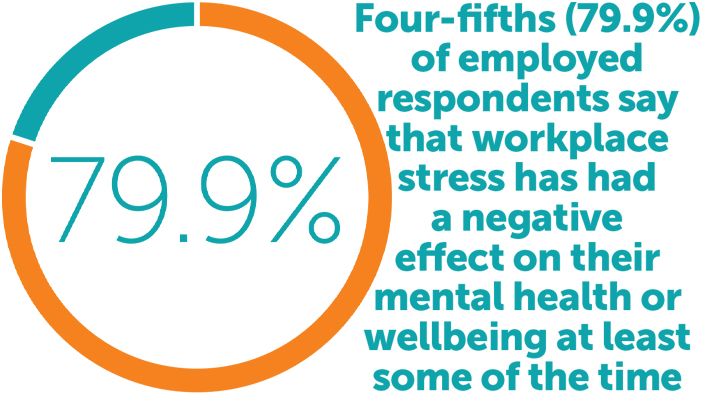

The consequences of increased stress are sadly inevitable. In 2020, just over half (53.7%) said workplace stress had had a negative effect on their mental health or wellbeing – now, four-fifths (79.9%) of employed respondents say it has had a negative effect on their mental health or wellbeing at least some of the time. More than a quarter (26.8%) say it has often had a negative effect, while one in 10 (9.5%) say it is a constant issue.

Andrew, a respondent, says he is “constantly worrying what the next problem will be, while trying to catch up on work. It’s like waves crashing into a beach, endless problems.”

The symptoms of stress are many and varied. Some reported depression and suicidal thoughts, while others developed physical issues such as high blood pressure or irritable bowel syndrome.

Many employees report sleepless nights and difficulty ‘switching off’, and it is easy to see how untreated stress can cause a dangerous feedback loop, described by respondent Tom as a “vicious cycle”. Disrupted sleep leads to irritability or loss of attention at work, and deadlines build up quickly, leading to more worries about workload.

“Sleep deprivation can lead to problems with punctuality and decision-making and may affect your mood too, potentially increasing irritability and frustration – particularly if you find yourself making more mistakes,” says Emma Mamo, head of workplace wellbeing at mental health charity Mind. “Sleeping too much can also be a sign of poor mental health and can result in feeling lethargic and lacking in energy.”

Under pressure

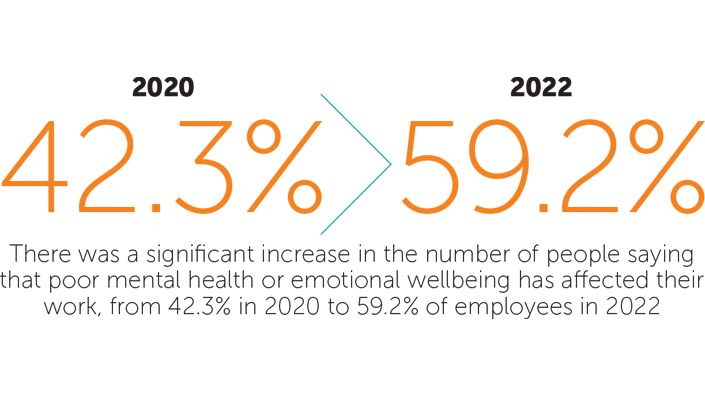

Stress can seep into all aspects of life, but the most immediate impact is often at work itself. There, too, things have got worse since 2020, when 42.3% said that poor mental health or emotional wellbeing had affected their work; this had risen to 59.2% of current employees in 2022.

Nearly three-quarters (71.2%) have gone to work despite feeling emotionally or mentally unwell, a slight increase from 67.5%. Of the current employees, a worrying 7.1% say it happens all the time.

“I can’t possibly achieve everything, so I’m struggling to bother with anything. But then I feel guilty and end up sitting at my desk for far more hours, but still not achieving much,” says a mechanical technology engineer. “I don’t feel like I have much of a life outside work, and yet I also feel useless inside work. It makes me feel pretty useless all round.”

Strategic thinking becomes much harder under intense stress and anxiety, sometimes resulting in a kind of mental paralysis – like a “rabbit in the headlights,” says Stephen, a director. Short-term solutions, poor decision-making and lack of concentration are particularly concerning for engineers working in safety-critical roles.

Tick-box exercises

With such high levels of stress, and the potentially devastating consequences, it might be expected that every organisation would put wellbeing front and centre. But almost one-fifth (19.7%) say their employers do not offer adequate support, while 28.7% simply do not know if their employers offer enough help.

Mental health ‘first aiders,’ self-check phone apps and external phone counsellors were among the support options offered to employees, but many were unconvinced of their usefulness.

“Company has appointed largely untrained members of staff as mental health ambassadors for the site,” says David, a respondent. “It’s wholly unclear to most of us what this is supposed to achieve, other than tick a management box whilst management continue with lay-offs despite an increasing workload and order backlog.”

Almost two-thirds (64%) now say their employers listen to work-related concerns, but more than two-fifths (42%) say they either do not know if their employers act on those concerns to prevent stressful situations, or that they simply do not act.

“I’ve asked for help,” writes one respondent. “No help so far. Things have only got worse as my subordinate has left, so now I’m on my own covering two jobs.”

Another person put it simply: “There are people to talk with... but talk does not resolve the structural problems.”

Structural issues

Despite the huge damage wrought by the pandemic, it was also the unlikely source of at least one positive change. For many, Covid-19 helped open up conversations about emotional wellbeing and mental health with colleagues and managers. More than half of current employees (55.9%) say the pandemic has changed discussions, with 87% of those saying they have become more open.

That openness can lead to improvements elsewhere, says Jo-Anne Tait, who researches the mental health of engineers at Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen. “There are practical things that I think can be utilised,” she says, giving the example of going for a walk to clear the head and aid decision-making. “If you’re having those conversations more openly, you get to that quicker, rather than waiting until someone has a meltdown. There will be a whole trail of stuff that’s come before that. If you can address it more clearly, you could be reducing burn-out.”

Employers offering assistance that addresses stress after it has already become an issue – instead of proactively preventing it with changes to workplace culture and work-life balance – was a common theme in both the 2020 and 2022 surveys, however. “Whilst there has been a significant increase in corporate awareness and communication to managers and employees, there still seems to be very little change to many of the root causes, such as more work with the same, or fewer, people,” says one respondent.

Employers need to survey staff regularly to identify and tackle work-related causes of poor mental health, says Mind’s Emma Mamo, making sure any initiatives are appropriate and easy to access. “Employees also easily see through tokenism and temporary measures, so employers must make a genuine, long-term commitment to creating a mentally healthy culture,” she says.

“A mentally healthy workplace is one where all staff – including disabled employees and those with mental health problems – feel able to talk about their mental health and know that, if they do, they will be met with support and understanding, rather than facing stigma and discrimination.”

Help is at hand

Ultimately, positive change must come from the top down. “I had a one-to-one ‘return to work’ meeting with my manager,” writes the mechanical technology engineer, following a few days off sick. “He spent 20 minutes pressing me to complete certain things and complaining that he doesn’t see enough output from our team.

“Having spoken to him again since, I realise he is himself under enormous pressure from his manager and just passed some of it on. So much of the source of our stress is structural.”

The IMechE can help members with counselling, social visits and other support. To apply for assistance or to help, contact the team on 020 7304 6816 or email supportnetwork@imeche.org.

The Institution is running an online Mental Health Awareness training session on 15 September. For more information, visit imeche.org/training-qualifications.

Get to grips with the future factory at Advanced Manufacturing (18-22 July), part of the Engineering Futures webinar series. Register for FREE today.

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.