But right now, a small company there named Rimac is building one of the world’s most exciting supercars; an electric beast destined to thunder to over 250mph.

In Italy, Pininfarina, a car manufacturer born before the Second World War, is doing something similar with a £1.5 million electric hypercar described as the ‘birth of a beautiful dream’. In the US, Tesla is working on its Roadster, which can bolt from zero to 60mph in under two seconds and, according to founder Elon Musk, will deliver a “hardcore smackdown to gasoline cars”, starting next year.

Over in Britain, Lotus is developing a mysterious new muscle car with an electric heart, Ariel is doing some “radical engineering” on its HIPERCAR (High Performance Carbon Reduction) and James Bond’s car maker of choice, Aston Martin, has just announced its first electric Rapide.

The world of electric supercars is somewhere between a Grand Prix and a Cannonball Run of new technology, engineering challenges and the quest to capture the soul of a growling V12 engine in the electric age.

Development in this niche corner of the much wider electric vehicle (EV) market is accelerating for several reasons, starting with the discovery of just how much punch an electric engine can deliver. (A family saloon car like the Tesla Model S can hit 60mph in 2.4 seconds, which was previously the sacred realm of Ferraris and Lamborghinis.)

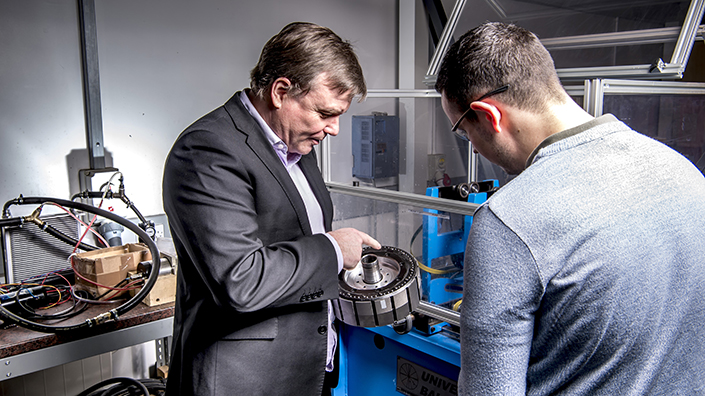

Ian Foley (left) is developing high-performance motors for the new breed of cars (Credit: Equipmake)

“People have realised that with electrification you can make a much more advanced product,” explains Ian Foley, managing director at Equipmake, a British engineering company building electric motors and powertrains. “You can have very high torque at all four corners of the vehicle, which means acceleration figures are higher than is possible with a conventional fuel car.”

Being able to use software to deliver this power to each wheel (torque vectoring) makes it possible to handle the car in new ways. An electric motor (or four) also delivers instant power without the need for an engine to rev up. The result is lightning-fast power to all four wheels with surgical precision. “The coming breed of electric supercars is going to be significantly higher performance than fuel cars,” says Foley. “They’re going to be better cars, basically.”

Capacity compromise

The discovery of this power potential has been made possible by advances in batteries and the chemistry that governs their ability to store and release energy. But there is a frustrating compromise between capacity and power release.

Paul McNamara, technical director of Williams Advanced Engineering, explains that engineers have to find clever solutions to this conundrum. In cars, he says, gasoline stores 15 times more energy than lithium-ion batteries. In other words, to match the energy and range of a petrol tank requires a bigger electric battery, which weighs down the vehicle and affects the way it handles. Range is also a major issue. “A modern electric powertrain and its challenges are probably 80% a mechanical engineering challenge,” McNamara says. “It’s a very exciting time. We’ve had a hundred years or more of the internal combustion engine and we are now at a transition that’s requiring a lot of new thinking and a lot of innovation.”

As batteries get smaller, lighter and cheaper, some of the key engineering challenges that remain include integrating them into car platforms and keeping the overall weight of the vehicle down. Fortunately, when cars cost £1.5 million or more – Rimac’s C_Two and Pininfarina’s Battista are both priced in this range – there is space to experiment with new technology.

“It’s easier for a car company to incorporate new (and thus expensive) battery technology without offending the potential buyer,” says Bob Sorokanich, deputy editor of US-based Road & Track. “An engineering solution that’s proven to work well in a supercar has a good chance of later being applied to more conventional vehicles. EV supercars present the leading edge of the future of automotive technology.”

Supercar technology could find its way into more affordable models (Credit: Pininfarina)

One of the other big hurdles is cooling electric engines to ensure they can provide steady, repeatable power. That’s where companies like Equipmake tend to step in. Foley, an engineer who has worked for Lotus and Williams Formula One teams, says water remains the best method to cool a hot engine or battery, but when there’s electricity involved, this becomes difficult.

To avoid degrading quickly, batteries need to be kept at cooler temperatures than internal combustion engines, Foley explains. This typically ranges from 40-60ºC. Using water and the air temperature to keep things cool is relatively easy, but liquids that conduct heat tend to also conduct electricity and so, for the same reason you wouldn’t throw a hairdryer into a bathtub, you can’t use water to directly cool an electrical system. Alternatives include using air alone or dielectric fluids like oil, which is used in power transformers.

For its motors and powertrains, Equipmake decided to invest three years into researching and developing a unique water-glycol system, which still uses water for cooling. The trick was to funnel the water as close as possible to the rotor and the magnets – which are arranged around it like the spokes of a wheel – without compromising the electronics. This work has led to a partnership with British car company Ariel on the HIPERCAR project to build a supercar known, for now, as the P40. The project has received more than £2 million in grants from, among others, the government’s Innovate UK initiative. Production is expected to start next year.

Equipmake, meanwhile, is itself moving from an R&D company to a production one with plans to move into new premises by the end of the year. Some of its other work involves electric buses and building prototypes of flying taxis.

Customised cars

Electric supercars are likely to benefit from futuristic thinking and rich imaginations. David Bailey, Professor of Business Economics at Birmingham Business School, says Additive Manufacturing can help car makers shed weight off vehicles by reducing the number of components and using different materials or combining existing ones.

He also sees a future where clients can customise or co-create cars through 3D printing (much like trainers or bicycles) and even print replacement parts when and where they are needed. Once established, printing parts allows for complex structures to be made relatively easily and cheaply, adds Foley, and is likely to have a major impact on the industry. At the same time, Bailey sees huge potential for integrating automation into the electric supercar.

“People may want to drive it around the track at the weekend, but have it in autonomous mode when they’re stuck in traffic,” he explains. “Also, autonomous technologies might be able to give the driver feedback on how they’re driving and correct them if they go into a skid on a corner. This may, at first glance, seem completely out of kilter with what supercars are about, but if it assists the driver in improving his or her performance, I think it could be quite interesting.”

The Chinese electric supercar, Nio EP9, has already demonstrated the potential of autonomous racing at a track in Texas. Just 19 seconds separated the laps the car ran in 2017 with and without a driver inside. Out on city streets, tests continue to merge the worlds of electric and autonomous vehicles.

Croatian company Rimac has pioneered the C_TWO electric car (Credit: Rimac)

Another trend Bailey is watching is the sharing of technology by supercar makers. Volkswagen, for example, has made its Modular Electric Toolkit platform available to other car makers. Porsche has invested in Croatia’s Rimac, which also sells its technology to clients like Aston Martin and Pininfarina (a direct rival). As companies compete and collaborate on the technology that underpins their individual models, the incremental changes, says Bailey, should drive down the costs of the tech and make it more accessible. For engineers, there are plenty of opportunities to learn new skills, retrain and help create supply chains. “If you’re in engineering and you’re developing these products, these are extremely exciting times,” he says.

Part of the excitement is the ability to reimagine cars, adds Paul Arkesden of engineering services company Envisage. This means completely new, lightweight architecture designed around new technology, with no legacy platform issues.

“I am really pleased to see the constant increasing popularity of STEM subjects and the exciting increase in the positive profile of STEM in the public domain,” says Arkesden. “It’s fantastic that the UK is leading the way not only in tech, but in funding and support by government and academia.”

While encouraged by the development of new batteries and materials (sustainable or organic composites), Arkesden, who previously worked at McLaren, says much of the hype around electric supercars and their performance is designed to grab headlines and build brands. He says the verdict is still out on whether EVs will truly go mainstream, especially in countries like the US.

Engines here to stay

On the supercar front, Bailey also doesn’t expect the internal combustion engine – the “mightiest motor in history” – to disappear any time soon. Although there are electric cars that can flood the cabin with artificial internal combustion engine sound, not all enthusiasts will be ready to let go of the “guttural roar” and “ripping metallic howl” of the V12. Beyond that lies something even more elusive… the feel, the smell and the legacy of the oil-spattered, man-versus-machine battle that rages on.

Electric engines may allow a Tesla Model S to rocket to 60mph in the same time as a Lamborghini or a Ferrari, but according to a recent CNN report, both these Italian car makers are not ready to change direction. Hybrid technology is being widely explored, but problems cited with pure electric versions include weight, range, packaging battery packs to ensure the right handling (keeping the driver low to the ground), the ability to accelerate at high speeds and around corners repeatedly and, yes, the “rich symphony of rapid-fire internal combustion”.

“Creating a supercar is much more than the development of a powertrain,” observes Roger Blakey, chief engineer of the Rapide E project at Aston Martin. “With the development of electric cars, even mundane family sedans can have amazing performance… but a supercar is more than a list of numbers. It’s about the driving experience, the interaction of the driver with the machine, the skill it takes to master it and the reward you get from doing so.”

Perhaps instant power and computerised control at each wheel goes against the unpredictable nature of motorsport and dilutes some of the adrenaline of taking a corner at high speed. For Aston Martin, a key part of creating the Rapide E – done in partnership with Williams Advanced Engineering – was to “enhance and build on the feel, character and delivery of the V12 engine”.

Older brands such as Aston Martin are also working on electric supercars (Credit: Aston Martin)

For Blakey, the evolution of EV technology is accelerating, and what was impossible a year ago is possible today. Solid-state batteries could help to further overcome the weight paradox. Universities like MIT in the US are experimenting with turning a car’s body into a supercapacitor by using carbon nanotubes to store electricity in the panels. Safety is improving with the use of carbon/Kevlar shells for batteries and smarter computer programs. Charging times are dropping and projects to roll out charging stations and supporting infrastructure are under way.

With new clean-air regulations and more awareness about harmful emissions, EVs are dominating global car shows, with offers from all the big names. Billions are being invested. In March, EVs outsold gas and diesel models in Norway for the first time. Volvo expects to make as much profit from electric cars as it does from gasoline ones by 2025. China accounts for about half the world’s EV sales and is furiously developing battery technology, driving down prices.

Even the most traditional affair in British life – the royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle (now the Duke and Duchess of Sussex) – had an electric twist, with the couple driving off in a 1968 Jaguar E-Type that had been unnoticeably converted to battery power. The roar of the electric revolution is growing louder.

“The automotive stage will be a different place in 10 years’ [time],” says Blakey.

Judging by the ambitions of Rimac, Pininfarina and car makers around the globe, it’s going to be a supercharged ride.

Read part two: "Aston Martin uses experience to build electric supercar."

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.