Cruising the loch aboard the ship on 14 August 2011 was Professor Isobel Pollock, then president-elect of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, with a party from the Institution’s Glasgow and South Western Area. They were there to present PS Waverley with the Institution’s 65th Engineering Heritage Award.

Professor Pollock presents the IMechE heritage award to the ship's then chief engineer Ken Henderson

When presenting the award to the ship, which is the world’s last seagoing paddle steamer, Professor Pollock noted that “It’s a testament to the great skill of the original shipbuilders, as well as the fantastic restoration work of the current owners, that after 65 years the paddle steamer is still going strong.” She was not wrong.

Paddling since 1947

PS Waverley’s keel was laid in December 1945 at the A&J Inglis yard, now the site of Glasgow’s Riverside Museum. The vessel was built for the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) to replace the 1899-built Waverley paddle steamer which was sunk at Dunkirk in 1940. Waverley was also the last Clyde paddle steamer to be built. After its launch in 1946 it was towed to Greenock to be fitted with its steam engine, a triple-cylinder compound of 2,100hp, the most powerful ever fitted to a Clyde paddle steamer.

After its maiden voyage in June 1947, the ship joined a fleet of 14 steamers offering popular trips ‘doon the water’. However, this fleet steadily decreased as car ownership increased so that by 1973 Waverley was the last of its kind on the Clyde. Caledonian MacBrayne withdrew it from service at the end of that season. However, instead of scrapping it, the company gifted the ship to the Paddle Steamer Preservation Society (PSPS) for a pound.

After much hard work and fundraising, the ship was back on the Clyde in 1975 under PSPS management. The society understood that the ship had to carry enough passengers to ensure its survival. As a result, between 1977 and 1979, its sailing programme was progressively increased to include Liverpool, Bristol Channel, the south coast and the Thames. Between 1981 and 1983 the ship circumnavigated Britain on three occasions to sail from east coast piers.

In 1999, with the aid of a lottery grant, the 52-year-old Waverley had a £7m rebuild. This included extensive re-plating, and overhaul of paddles, engines and auxiliary machinery. Great care was taken during the rebuild to preserve the ship’s heritage. However, one part of the ship not seen by passengers was significantly changed. This was the boiler room into which two new Cochran boilers replaced a single Babcock Steambloc boiler.

When it was fitted in 1981, the Babcock boiler gave a 23% fuel saving. It replaced the original double-ended Scotch boiler which had six furnaces, three at either end. This is why the ship has two funnels, although since 1981 only one has been used for boiler exhaust. The Scotch boiler was originally coal-fired. It was converted to oil firing in 1956.

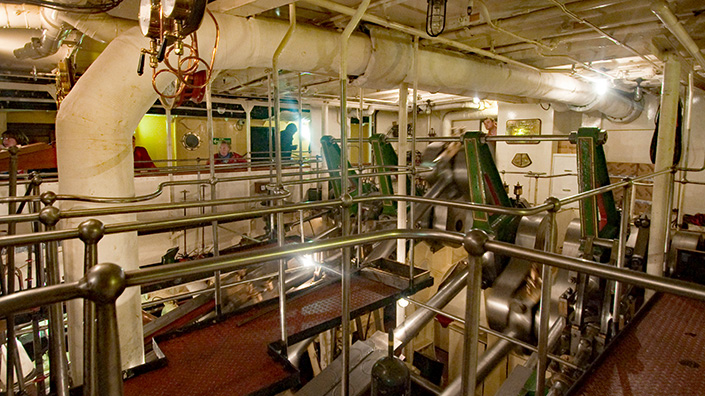

Machinery and systems

The Cochran boilers are three-pass wetback units with fuel burnt in a furnace tube and exhaust gases passed through two sets of boiler tubes. Each boiler holds 20 tonnes of water and can generate 5.5 tonnes of steam per hour at a pressure of 180psi. At this rate, both boilers consume 700 litres of fuel per hour. The high-, medium- and low-pressure cylinders of the triple-expansion steam engine have cylinder diameters of respectively 24, 39 and 62 inches and operate typically at 130, 35 and 0psi. This low-pressure cylinder operates at atmospheric pressure because its exhaust pressure is –12.5psi owing to condensation of the steam.

Unlike railway steam locomotives, the steam is recirculated and so needs to be condensed before its condensate is fed back into the boiler. The engine delivers its maximum power of 2,100hp at 58rpm. It normally operates at 46rpm to give a cruising speed of 14 knots.

The main engine is just one of 11 steam engines on the ship which include various steam-driven pumps, the winch, capstan and steam tiller which is fixed to the rudder stock. The steam tiller moves with the rudder to the required position as its engine drives a pinion engaged with a fixed toothed quadrant rack. The ship’s wheel moves a hydraulic cylinder which controls a hydraulic cylinder in the steering compartment to operate the steam tiller’s valve gear.

Each paddle wheel has eight timber paddle floats, 11ft wide by 3ft deep, and has a feathering mechanism to keep the paddles close to vertical as they enter the water. The floats are 13ft 10in in diameter to the float centres and weigh 8.5 tons. At 42rpm, the floats move at 30ft/sec, compared with the ship’s 24ft/sec through the water at normal cruising speed. In reverse, the speed difference between paddles and the water, together with the size of the floats, accounts for the ship’s high deceleration.

One of a kind

Running a paddle steamer today is a complex operation. As Waverley is quite different from a conventional ship, it is difficult to apply modern marine legislation to it. Its operation is also costly, with high fuel, maintenance and staffing costs. Unlike preserved steam railways, it cannot be operated by volunteers or run at weekends only as it can only sail with a fully certified crew of more than 20 officers, seafarers and engineers who live aboard the ship.

The Waverley’s operation is unique, with engine commands from the bridge transmitted to the engineers by a ship’s telegraph. Its handling differs from other ships as the rudder, with no propeller in front of it, is ineffective at low speed. However, with its large paddles it has much greater deceleration than other ships. So, to maintain its steerage, Waverley must approach piers faster than other ships and then stop quickly. Ropes then position the ship against the pier using the steam-driven windlass and capstan.

A crew of more than 20 keeps everything shipshape below deck

This specialised operation must take account of varying winds and tides and requires effective teamwork between the bridge officers, engineers and deckhands. When docking, the engine room alleyway is the place to see the duty engineer controlling the engine in response to telegraph commands from the bridge. Unlike railway steam engines, the reversing gear is steam driven as it must operate instantaneously when approaching piers.

During the winter months, Waverley’s engineers and volunteers maintain the engine, boilers, paddles and deck gear while the ship is moored at Glasgow. This involves surveying, repairing and rebuilding machinery in accordance with a five-year survey programme. This is demanding work, especially as the ship is the only one of its kind and the Clyde shipyards, where specialists maintained specific components, are long gone. The ship is also dry-docked for two to three weeks for its mandatory out-of-water hull survey, painting and repairs that cannot be done when moored in Glasgow.

Survey reveals cracks

During the 2018-19 winter, maintenance work included paddle wheels, main engine bearings, the main steam regulatory valve and the second 10-year boiler survey. During this survey cracks were found in the starboard boiler furnace hoop which initially were deemed repairable. However, metallurgical analysis and the requirement for patch repairs to overlap previous patches used to repair cracks when contaminated fuel overheated the boiler a few years ago revealed that the only possible repair was the replacement of a 360-degree boiler hoop.

This could not have been completed until at least halfway through the season and further metallurgical analysis indicated that cracks might propagate after this repair. Because of this, and other possible unknowns, it was decided that new boilers were required to give the ship a long-term future.

£2.3m boiler appeal

The ship’s 2019 sailing programme was therefore cancelled and, in June, a £2.3m appeal was launched to replace the boilers and other boiler-room equipment while the top decks are removed for this operation. By August the boiler appeal had raised £500,000 and the new boilers were ordered. The programme envisages the boilers being replaced between January and April 2020, ready for the sailing season. Achieving this programme is dependent on funding but is essential if the ship is to survive as an operational vessel as this requires income from the 2020 sailing season. In September, the Scottish government announced that it was donating £1m to the boiler appeal to add to other donations of £800,000. While this makes the ship’s survival more likely, substantial funds are still required.

Seventy years ago, the LNER provided today’s generation with a unique attraction for anyone with an interest in ships, scenic cruising and industrial heritage. It also offers one of the few public opportunities to closely observe large mechanical plant operating at full power which may well inspire future mechanical engineers.

If you wish to help Waverley survive, visit www.waverleyexcursions.co.uk to learn how you can contribute to the boiler refit appeal.

Want the best engineering stories delivered straight to your inbox? The Professional Engineering newsletter gives you vital updates on the most cutting-edge engineering and exciting new job opportunities. To sign up, click here.

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.