The development of autonomous machines such as robots has brought great benefits to manufacturing. For jobs that require high levels of accuracy and repeatability or are simply too dangerous or boring for people to carry out, robots in, say, a car plant offer a welcome solution.

But increasing reliance on automated, or semi-autonomous, technology in other areas is giving some engineers cause for concern. One of these is in defence, where newspaper headlines frequently highlight strikes made by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or drones against targets on the Afghan-Pakistani border. These technological marvels, seemingly unerringly precise, have allowed US and British forces to engage in asymmetric warfare – that is, countering a terrorist-type threat – in previously unheard of ways. But some experts are questioning the morals of using robot-like systems to make these strikes – and they are worried about the path the technology may lead us down.

Among these voices is British academic Noel Sharkey, an expert on robotics from the University of Sheffield’s department of computer science who co-founded a pressure group, the International Committee for Robot Arms Control (ICRAC), last year. The organisation recently brought together experts from all over the world and representatives from government, the defence industry and humanitarian groups for a conference in Berlin where the issue of the ethics and proliferation of automated defence systems was discussed.

Professor Sharkey, as his position would suggest, is no Luddite. “The actual technology of say, UAVs, is nothing short of miraculous,” he says. “I admire it as an engineer, and it’s doing robotics a lot of good.”

But he is worried that the ethical dimensions of using systems such as unmanned drones to attack insurgents in Afghanistan are not being given due consideration. Such attacks may, he believes, contravene the rules of war and the principles of internationally accepted humanitarian legislation such as the Geneva Convention. Further, this form of warfare is already pitching countries into a new arms race, with many nations either buying or developing UAVs for military purposes.

Sharkey explains: “The cornerstone of the Geneva Convention is the principle of distinction, which means that a weapon has to be able to discriminate between a friend and a foe. Another key principle is proportionality – any collateral damage must be proportional to the military advantage gained.”

He believes that UAV and drone attacks are causing unacceptable levels of innocent casualties even as the final judgments on whether to attack are being made by human commanders at, say, an air force base thousands of miles away in the Nevada desert. He argues that increasing the autonomy of such systems is a stated desire of the military and that the development of completely autonomous military robots (such as, for example, BAE’s Taranis system) on the ground, in the sea or in the air can only compound the ethical dilemma.

“Proportionality is notoriously difficult to judge – there’s no metric for it and it’s up to a human commander to make that call,” he says. “My worry is that no robot or software can do that: it can’t distinguish between combatant and civilian.” Mistakes, he notes, are already being made with humans making the final call.

Professor Alan Winfield of the University of the West of England is another expert on robotics and is carrying out pioneering research into developing machines that can work comfortably alongside humans [see box]. But he is well aware of the limitations of robotics. “The idea that you can develop a machine that can distinguish between friend and foe is fantasy,” he argues. “In the fog of war, even human soldiers have enormous difficulty sometimes making that judgment. And our technology is not good enough to be able to tell the difference between a child with a toy and a youth with a weapon.”

But semi-autonomous and perhaps ultimately completely autonomous military hardware is attractive for a number of reasons. It reduces cost, eliminates some of the risks of combat, and can be trained on specific targets. Sharkey says: “All the military roadmaps are pointing to autonomy in a big way. The desire is to develop fully autonomous operating systems on the ground or in the air, with the aim of creating completely risk-free warfare.

“The drones flying around might seem expensive to us – but that’s really a fraction of the cost of a manned fighter jet.” He claims that the US trained more ground-based pilots for remotely operated UAVs than pilots for combat jets for the first time last year. He is not anti-autonomous technology per se, but would like to see more resources devoted instead to developing automated systems that could search out and disable bombs on the ground. “That would save lives on the roads of Afghanistan,” he says. Winfield concurs: “I strongly support the case for developing robots for looking under cars for explosives and searching for landmines, for example.”

In terms of future international security, developed nations are eyeing technology that could counter more technologically sophisticated enemies than the Taliban or terrorists in Somalia or the Yemen. Sharkey suggests that the human control over UAVs, which involves satellite and radio communication, could be jammed relatively easily by technologically advanced nations such as Russia or China. The delay between operator input and the command being carried out by the UAV also makes it unsuited to dogfighting and easier to shoot down. Sharkey says: “With unmanned drones, you’re working at a delay all the time – and that also means that the people making the decisions on who to kill are having to make them very quickly.

“Fully autonomous craft could make decisions much quicker than a human could at the speed the craft was travelling. The possibility of jamming the signals controlling UAVs by advanced nations such as Russia or China is one reason why autonomy is likely to increase in importance.”

He is not calling on the engineering community to give up developing autonomous military vehicles or university engineering departments to refuse to accept funding from the defence industry, he says.

“I’m not saying to my colleagues, ‘don’t take military funding’, but I am saying, ‘please be truthful about the limitations of the technology’. Engineers are good, ethical people and they abide by the professional codes of ethics given to them.

“But in some cases, we’re only beginning to look at the moral implications of the artefacts we are producing. There is a responsibility not just to the military customer but in terms of a consideration of how the technology is to be used.”

Nature calls in push to develop artificial intelligence

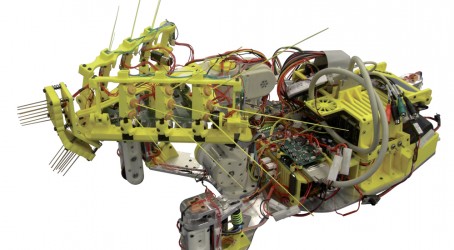

Professor Alan Winfield of the University of the West of England has been engaged in research to develop robots inspired by nature that could work effectively alongside human beings. Some of these are based on group behaviour exhibited by swarms of bees or ants.

Artificial intelligence, he believes, has had something of a chequered history and its early promise has not been fulfilled in the manner some had envisaged decades ago. He points out that while it has been possible to create rules-based computer programs that can challenge a grandmaster to a game of chess, it has proved relatively difficult to make a robot that can usefully co-exist with human beings or even carry out domestic chores.

“Machines as smart as, say, an iguana, are still a long way from being built,” he says. Another pertinent analogy, he suggests, concerns passenger aircraft: autopilots may do a lot of the work but airliners are still required to be flown by two pilots.

Aside from concerns over the use of robots by the military, he believes designers of robots for consumers must consider the impact their creations can have on the vulnerable such as young children, who can become very attached to technological gizmos – as any parent who has video-game-addicted children will testify.

Winfield says: “Uniquely, robots can bring together the power of humanoid agency – the ability to do something – with potent emotional appeal, such as being able to look you in the eye.

“That can be very appealing. An ethical dilemma that designers and manufacturers of robots face is if their products create a dependency that is unhealthy in the young or vulnerable.

“My concern is that you can’t make an ethical robot. But what we should be looking for as robot designers and engineers is to behave ethically. And that includes manufacturing.”