The nuclear new-build programme has been promising to reinvigorate the nuclear supply chain in this country for years. But since the government gave the go-ahead for a new generation of nuclear power stations in early 2008, there have been a series of setbacks.

The fallout from a tsunami hitting the Daiichi nuclear plant in Fukushima, Japan, in 2011 sparked concerns over safety that led to a lengthy review of the nuclear new-build programme.

Then in March last year, RWE npower and E.on UK shelved plans to build new nuclear power stations at Wylfa on Anglesey and Oldbury in Gloucestershire, pulling out of their Horizon Nuclear Power joint venture. They said new nuclear power stations were costly to finance and gave only long-term returns on investment. Japan’s Hitachi has now stepped forward in a £700 million deal to buy Horizon, with plans to employ advanced boiling-water technology reactors at the sites.

By September, rumours were rife that Spanish firm Iberdrola was withdrawing from its nuclear consortium with GDF Suez, known as NuGeneration. The speculation cast a shadow of uncertainty over the group’s plans to build a new reactor at the Moorside site near Sellafield in West Cumbria. A year earlier, SSE Energy sold its 25% share in NuGeneration.

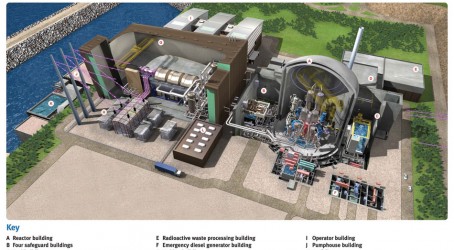

But against this backdrop, French company EDF Energy’s plans to build two European pressurised water reactors (EPR) at Hinkley Point in Somerset have finally started to gather pace.

Late last year, there was a flurry of activity surrounding the venture. In November, the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) granted a nuclear site licence to NNB Generation Company (NNB GenCo) – a subsidiary of EDF. This came after a three-year period of consultation with NNB GenCo to assess its suitability, capability and competence to install, operate and decommission a nuclear facility.

Hot on the heels of that announcement came the nod from regulators in December that EDF and Areva’s EPR design was suitable for construction in the UK. The decision came after the generic EPR design had been subjected to a five-year assessment by the ONR and Environment Agency that covered 17 technical areas, from civil engineering to reactor chemistry. The £35 million review found that the design met regulatory expectations on safety, security and environmental impact.

But sandwiched between these two project milestones was another that generated far fewer headlines but was of great importance to British industry. A group of 25 nuclear suppliers gathered in central London to sign memorandums of understanding (MOU) with Areva, the company producing the EPRs for EDF.

The MOUs pre-qualify each company to potentially supply their products to the project. The suppliers covered a wide range of products and services, including forgings, valves, pumps, cranes, electronics, piping and tanking. In total, the deals are set to be worth £200 million and could pave the way to supply Areva for future projects in the UK and worldwide. With 20-50 new nuclear plants planned here alone by 2050, the stakes are high.

One of the companies that has pre-qualified to supply Areva is Centronic – a radiation detector manufacturer in south London. The company makes several types of detectors that are used in core reactor control, radiation and area monitoring, health physics and critical alarms. But the focus for any potential contract with Areva would be reactor control detectors, according to the company’s chairman, Neil Foreman.

These detectors are used for monitoring radiation, from reactor start-up right through to power generation. Initially, a source range detector monitors the activity of the reactor before the control rods are removed to power up the reactor. An intermediate range detector monitors the flux in activity as the reactor ramps up to full power. Finally, a power range detector monitors the performance of the reactor once it is running at full power.

Centronic is the only company in the UK to produce these types of detector, and supplies the nuclear industry worldwide. The company has worked with Areva in the past, including on a reactor in Loviisa in Finland. But the company still had to go through the supplier accreditation process to qualify for the EPR project at Hinkley Point.

“Areva is looking to make sure it has a good supply base in the UK,” says Foreman. “It helps it satisfy the demands of not only the political side – building a fleet of reactors in the UK using local suppliers – but also the nuclear inspectorate. It says you have to see a certain amount of capability in the UK to support the technology.”

As part of the process, an official from Areva visited the company and performed audits on its processes and capability.

Foreman says that the opportunity for the company is significant. “It is all part of the general accreditation process for the nuclear industry worldwide.”

Valve manufacturer Flowserve has also been pre-qualified by Areva to potentially supply the project. Its valves can be found in all types of power plant, but those used in nuclear are subject to specific certification criteria. To pre-qualify, the company completed an online questionnaire, which covered the company’s capability and stability, product quality and certification, health and safety, and environmental issues, as well as the scope of supply.

Flowserve’s area sales manager for defence and nuclear, Simon Carter, says: “The value would be fantastic. Its a major programme that we have been tracking for years.”

Winning a contract would see Flowserve looking at new facilities and taking on more engineers, although the scale of these measures remains to be seen, he adds.

For valve manufacturer Weir, the potential of any deal with Areva is already mapped out. In-house analysis suggests that Weir stands to gain an extra £20 million in turnover every year from the UK nuclear new-build programme as a whole. The move would enable the company to create an additional 200 jobs and a further 800 in the supply chain, says Ian Tough, internal sales manager for nuclear at Weir’s power and industrial division.

“The interactions we have had with the rest of the industry are all positive – there is a real drive from the big names to push this forward. It opens up further opportunities in the EPR and pressurised-water-type reactor markets. We are hopeful for the future,” he adds.

Weir has already worked with Areva on several projects, including EDF’s new reactor at Flamanville in France – the first reactor to be built in the country for 15 years. The French office of Weir’s power and industrial division has deployed pressurised safety valve and high-technology pilot-operated valves at Flamanville and other sites.

On the back of this work, the company has been in discussions with Areva about tweaking the design of a main steam isolation valve, manufactured in Elland, West Yorkshire, to meet the EPR’s requirements. The work has been ongoing since 2010 and has culminated in the recent MOU signing.

The 32in valve features a gas hydraulic actuator and is used on the main steam line from the generator to the turbine. “We’ve manufactured quite a few of these for China in recent years. With the requirements for an EPR, we’ve got to go through a new set of qualification testing specifically for Areva,” says Tough.

Looking to the future of nuclear new-build, he says one of the challenges that Weir and other suppliers will face will be determining and understanding the codes and frameworks to be put in place on the project. UK supply chain companies are also grappling with how to win business over established suppliers at Flamanville.

As the opportunity comes within touching distance, another hurdle may be finding suitably qualified staff, or people capable of learning to the required level. “There hasn’t been a nuclear new-build programme in the UK since the 1980s, so a lot of the manufacturing industry for nuclear moved to Europe and the US,” says Tough. “Hiring is a real issue for us. It is a difficult market to try and find people who are experienced in what we need. There isn’t a ready pool of people available to start tomorrow.”

To address this skills gap, Weir is working with Rolls-Royce, the Nuclear Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre in Rotherham (see box) and training programmes so it can establish what the requirements will be and put measures in place to meet them.

Although nuclear manufacturing may have gone elsewhere, skills in system design engineering and operational engineering in nuclear have remained here, says Tough.

Centronic’s Foreman says the UK industry already has skills and experience with the advanced gas-cooled reactors, as well as with a nuclear submarine fleet. The arrival of new Areva EPR technology, and potentially the GE Hitachi technology, will mean that the supply chain is qualified across a wide variety of technologies.

“From the UK point of view, this is good news,” he says. “Longer-term, it should lead to business for the company but, more importantly, for the global supply chain.”

Any contract with Areva would enable Centronic to retain and recruit individuals with the specific skills required in the UK nuclear industry. The company has to look for good engineers and then adapt their skills for the nuclear environment, says Foreman.

This strategy usually means that the company needs long-term horizons to plan recruitment, which could be possible if it wins the business. For the supply chain to plan long-term, the nuclear-new build programme needs to run smoothly. “We need to try to make sure there are no more delays to the programmes, that the complete supply chain is still in place when these contracts are let,” he says.

Delays can be a blow for UK companies that are not part of the global nuclear supply chain, or that do not work in decommissioning and waste management as well as new-build, he says.

The civil engineering stage of the project is still three years away, and only once this is under way will equipment contracts be let.

There are further obstacles to overcome in terms of affordability, says Foreman. To put the technology in place, operators need some level of certainty on the return on their investment in terms of the electricity price. “But overall, the future looks bright,” he says.

The final investment decision by EDF is in an “advanced stage of readiness”, says Humphrey Cadoux-Hudson, managing director of new-build at the company. Once this decision has been made, a further 25 suppliers could become pre-qualified.

“The responsibility is now with the government and us to provide a credible contract for low-carbon electricity – this is a prerequisite for us to go ahead,” adds Cadoux-Hudson.

Research centre helps companies to win orders

The Nuclear Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (AMRC) is part of the Advanced Manufacturing Park between Sheffield and Rotherham in South Yorkshire. Established in 2009 with government funds, it aims to raise the cost competitiveness of the UK civil nuclear manufacturing supply chain.

“We are after a capable and reactive supply chain that understands the requirements of Areva and Rolls-Royce in terms of cost, quality and time to delivery,” says Steven Court, the Nuclear AMRC’s operations director of nuclear. “We want to help prepare companies to qualify, pre-qualify, win orders and become part of the global supply chain.”

The 8000sq m building hosts a range of state-of-the-art machining centres, welding cells, virtual reality facilities, and other manufacturing, and research and development equipment tailored for nuclear industry applications. The Nuclear AMRC is working with quality assurance providers to ensure that companies in the supply chain understand quality requirements, and the codes and standards they must meet.

On the progress with Hinkley Point, Court adds: “This is good news for the UK-based supply chain. The time is now to prepare – put in the hard work that is needed to win orders at Hinkley Point and beyond.”