The second largest engineering project in the UK after the Olympic games is proceeding as planned at sites around the country. This is the building of two new aircraft carriers – the largest warships ever constructed here – by a partnership known as the Aircraft Carrier Alliance (ACA), which comprises BAE Systems, Thales, Babcock Marine and the Ministry of Defence.

The project survived last year’s strategic defence review unscathed but it was not always clear that the government would go ahead with the plan to build two carriers – or even one. David Downs, ACA engineering director, recalls: “I wasn’t particularly involved in the negotiations that were going on, I was keeping focused on the day job: we had a contract to design, engineer and deliver two aircraft carriers so that was the priority. But I think it would be fair to say that those that were involved – the commercial people – probably weren’t that confident.”

Fast forward to 2011 and work on the Queen Elizabeth class carriers is progressing rapidly. The two ships being built, HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales, are intended to replace the older Invincible class of aircraft carrier and will each provide four acres of mobile military base when they enter operation at the end of the decade.

Downs, a naval architect with many years’ experience in the shipbuilding industry, explains: “Clearly the Invincible class of aircraft carriers was designed many years ago for a particular threat. If you go back in history, the carriers were initially designed as helicopter carriers to support anti-submarine operations in the North Atlantic.

“These days the Cold War is over and our issues are different. The purpose of the aircraft carrier is to provide a few acres of sovereign territory, be deployed at any point and time of our liking anywhere around the world.” The Queen Elizabeth class is much bigger than its predecessor Invincible and can carry more aircraft.

The recent history of the wars in which Britain has been engaged, such as the Falklands conflict and the two Gulf wars, demonstrated the desirability of being able to deploy air cover exactly where it is needed at short notice and in situations where air bases are not available. Downs says: “So the rationale for the Queen Elizabeth class is very different to the rationale for the Invincible class. It is to be able to deploy worldwide to carry out a multitude of operations – anything from disaster relief through to full carrier strike operations, with a variety of aircraft types from rotary wing to fast jets.”

The two carriers will weigh 65,000 tonnes, have a length of 280m and a speed of 25 knots. With a full complement of crew, including aviators, they will carry 1,600 personnel. They will carry a variant of the Joint Strike Fighter designed for carrier operation, although not the short take-off and vertical landing (STOVL) version of the JSF originally envisaged, which was a casualty of the defence review. This means that a system of “cats and traps” will now be required to launch and land the aircraft. Peter McKell, head of the carrier project at BAE Systems’ shipyard on the Clyde by Glasgow, where some substantial sections of the two carriers are being manufactured, explains that the engineers are likely to opt for a US-designed electromagnetic cat and trap system rather than traditional steam-driven catapults. “It’s much more modern. The disruption in terms of incorporating huge boilers into the vessel would be significant.”

Downs adds: “It is some pretty high-tech equipment that will be procured from the US and integrating it safely and making sure it is capable of being operated on the aircraft carrier design presents some pretty significant challenges. But we have the space and the basic provision in the ships for the kit. The actual physical integration of them is going to be quite a significant challenge.

“And I suggest it will be a challenge for the Royal Navy in developing people qualified to operate and fly them.”

Also innovative in terms of the carriers’ design is the decision to include two “control islands” on each vessel rather than one. A single island would typically contain both the bridge and air command on a carrier but on the Queen Elizabeth class these will be separated into two structures, both of which are being built by BAE Systems in Glasgow and at the company’s other shipyard in Portsmouth. Downs explains: “There’s an advantage for visibility in getting the bridge as far forward as possible. And there’s an advantage from a flight control point of view in having the aviation island at the business end of the flight deck, which is where the aircraft will start their take-off run – even if the aircraft were STOVL, it would have been the same location.

“There was considerable concern about the flight command and the bridge not being co-located: that the flight controller or the captain couldn’t just wander through and talk to the other guy – so we’ve had to do quite a lot of work in terms of proving communications, and there’s been some practical studies on HMS Illustrious in terms of putting a bulkhead between the two and seeing how they got on.”

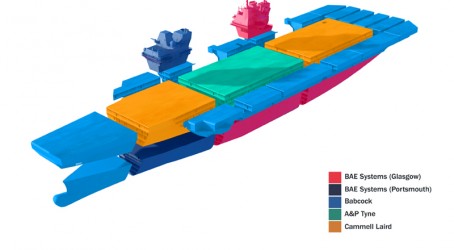

The Queen Elizabeth class programme has many partners both in terms of the principal contractors and suppliers. As well as BAE, Thales and Babcock Marine, A&P Tyne and Cammell Laird are constructing elements of the ships. Downs asks: “Is it a challenge to coordinate that? Yes. I don’t think there was any one organisation in the country that had the ability and the capacity to have done the design or the build of these ships independently.

“Designing them in two locations, engineering them in four and building them in six is perhaps not the way that you would choose to start a major project, but in reality it was probably the only way it was practical to do it. And therefore we do have to rely on shared data environments, computer tools and interface management to make sure that everybody’s pointing in the same direction and knows what’s going on.” McKell adds: “From what I’ve seen from my short time involved with this project, this is definitely an alliance, a collaborative view with collaborative behaviours too. It is something you might not expect given that these are all independent commercial organisations with their own aspirations.”

McKell is overseeing the production of monolithic “blocks” of the carriers at BAE on the Clyde. HMS Queen Elizabeth is being built first with HMS Prince of Wales following in her wake. The company cut the first steel for the second carrier in May. BAE is building three of the biggest sections of the carrier at the Clyde and in Portsmouth. It will also build the aft island on the Clyde, a change of strategy. The first block to be finished, known as Lower Block 03 (LB03), is due to be transported later this month to Rosyth naval dockyard on the Firth of Forth – the opposite side of the country – where final assembly will take place.

Wandering around the gangways and up the ramps and ladders of LB03, which in itself will weigh more than a Type 45 destroyer when fully kitted out and manned, is quite an experience. The cabins – there are 185 cabin modules – have been installed bar carpets and televisions and the weapons decks have been fitted out. BAE engineers and workers scurry about their business, making final preparations on the giant. LB03 will require what is said to be one of the largest barges in the world to transport it. It will require two weeks of work to fasten the block to the barge, and then it will be transported around the north of the country to Rosyth. Once it arrives there, other upper blocks will soon be added as HMS Queen Elizabeth begins to come together as a whole.

The scale of the project is what makes it special, says McKell, who has been working at the Clyde shipyard for 36 years and been involved with many programmes including the Type 45 build. “This is not the same as building a ship on the Clyde where it’s a full programme: where we manufacture, assemble and integrate weapons and propulsion systems here and take the vessel out on trial. Setting a complex warship to work is no mean task.

“That will happen in Rosyth for the new carriers, but that’s not to undermine what we are doing here. It’s the scale of this project – no one organisation could take it on on its own without these alliances and partnerships.”

So somewhat ironically, while shipbuilding in the UK is not thought of as a major industry, the sector is still carrying out one of the biggest projects it has ever entertained. A government decision not to build the carriers would have been a bitter blow for Glasgow, says McKell. “It would have decimated the British shipbuilding industry. And it could have brought about the demise of UK warship building.”

Downs concurs: “If that decision had come to pass it would have been bad. There are an awful lot of people employed on the carrier programme both on the ACA sites and companies in the supply chain. Without the carriers there would be a lot of people with nothing to do.

“I think the carriers will prove to be a major legacy for the country, both in terms of our ability to react to situations worldwide, but also in terms of a showcase of British industry.”