Strength test: The hide, with Gordon Buchanan inside, was attached for 40 minutes

Being asked to “ensure it can withstand a polar bear attack” is one of the more unusual product design briefs an engineer is likely to receive. But that was what mechanical engineer Roger Usherwood was told to bear in mind when designing and manufacturing a photography hide for a BBC Natural History television production to be filmed in Svalbard, in the Arctic.

The series in question was The Polar Bear Family & Me, which aired on BBC2. Much of the programme’s stunning close-up footage of the bears, captured by wildlife cameraman Gordon Buchanan, was shot from inside the hide designed by Usherwood – who is retired but was previously technical director for sieving and filtration specialist Russell Finex for 20 years, after gaining experience in tube-making and heating systems.

The initial specification was for a transparent hide that could be fitted to a sledge, says Usherwood. This would enable the photographer to easily observe the bears and be transported quickly to other locations while still inside. The hide would also need to provide a protective barrier between Buchanan and the bears should anything go wrong.

“Safety was a key requirement,” says Usherwood. “It was difficult to decide what stresses and strains should be accommodated, so it was just a case of making it as strong as we could.”

He decided to approach the project using traditional engineering techniques. His first outline design was a simple, rectangular structure using square steel tubes for the frame and polycarbonate panels as infill. However, the steel tubes were quickly swapped for aluminium to make the hide as light as possible.

“It needed to be light for two reasons,” he says. “Firstly, the final leg of the journey from Bristol [where the BBC Natural History unit is based] to Svalbard would be made in a relatively small helicopter, and each piece would have to be loaded and unloaded by hand. Secondly, it had to be assembled by the team in snowy conditions, wearing gloves and anoraks.”

Aesthetic considerations altered the design, too. It was not just the polar bears that would be shown on screen, but also Buchanan inside the hide. So the hide should be interesting to look at, it was agreed.

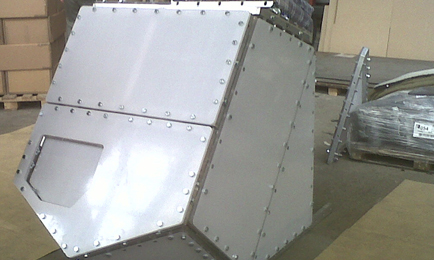

Usherwood’s basic sketches then had to be transformed into manufacturing drawings. “A parade of suitable companies was held from which an industrial designer, Michael Butler, was selected,” says Usherwood. “He used 3D CAD to produce a set of manufacturing drawings, and improved the appearance.” It was designed in seven sections which when locked together with the sledge as a base, became a rigid, eight-sided, monocoque-style structure.

With the design agreed, it was back to practical considerations. Usherwood and Butler held a meeting at the BBC with Gordon Buchanan, along with a polar bear expert and other film crew members, to refine the dimensions. The door and camera aperture were adjusted so Buchanan could easily get in and out and operate his camera comfortably and safely.

At this stage, one problem remained: how to make the hide polar bear-proof. The bear, which can weigh up to 600kg and stand 3m tall, is one of the most powerful and intelligent predators on the planet. If it decided to attack, the hide would need to be able to withstand a massive force.

In building the hide, a balance had to be struck between making the structure as strong as possible and its size and weight limits. The team also faced the problem of testing. How could they simulate a polar bear attack, and what impact energy should be factored in to the design?

“As no testing was feasible, and no data available on the forces or impacts, the specification became simple: just make it as strong as possible within the size and weight constraints, which is what we did,” says Usherwood.

Bristol-based plastic fabrication company FR Warren provided the team with precisely cut 12mm polycarbonate – the maximum thickness available. The team also opted for 12mm bolts – the largest that could be used without significantly weakening the aluminium sections.

KAM Engineering in Trowbridge manufactured the aluminium sections, using the latest CNC technology, and ensured they were made as large as possible, within the weight restrictions, to further reduce any potential weakness in the frame. The final maximum dimensions were 1,200mm x 1,000mm, and the maximum overall weight was 160kg.

All the parts could be trusted to remain strong in Britain’s 20ºC temperatures, but the hide design had to account for the stresses and changes that the materials would undergo in the sub-zero conditions of Svalbard. “Polycarbonate loses two-thirds of its impact resistance at -30ºC, and aluminium tube and polycarbonate shrink at different rates,” says Usherwoood.

“A temperature difference approaching 50ºC can make a significant difference. You need to take it into account when calculating the clearance, so that the bolt holes in the frame and polycarbonate will line up at +20ºC and -30ºC.”

On location: The ice cube in Svalbard

When the parts had been made, Usherwood, Butler, and Buchanan spent several days at KAM practising the assembly of the hide – christened the ‘ice cube’ – and made minor adjustments. It was then dismantled, packed in seven boxes, along with spare parts, and shipped to Svalbard – first by lorry, then by large aircraft, small plane and, finally, helicopter.

However, no strength tests were carried out on the ice cube before it left the UK. “There was a certain amount of flying by the seat of our pants,” says Usherwood. The risk to Buchanan was not taken lightly, and a ‘safety net’ of polar bear experts, familiar with methods of distracting a dangerous animal, accompanied him into the field.

Before the hide was assembled in Svalbard, the only physical test was carried out. The strongest member of the crew used a sledgehammer to try to break a 500mm square section of polycarbonate. To everyone’s relief, the sledgehammer just bounced off.

Although this approach to health and safety may seem cavalier, the team were confident the design would withstand an attack – as long as it was short-lived, says Usherwood. “We all thought that if a 1000lb, or bigger, polar bear had as much time as it wanted with the hide, it could probably tear it apart. However, it would have taken it a long time to do so, and we were confident that the safety team would scare it off.”

After the hide was assembled, it was towed to a position 50m from a seal breathing hole in the ice, where Buchanan waited for a bear. However, when a bear did arrive, “it decided there was more chance of a meal inside the hide than at the breathing hole”, says Usherwood.

The bear attacked the hide for what must have felt like an extremely long 40 minutes. But the ice cube team’s engineering skills meant the hide withstood this ultimate in strength tests. And while the attack certainly increased Buchanan’s heart rate, it also enabled him to get some incredible close-ups of the bear.

While Buchanan’s stunning photography and footage went viral, the press could have said more about the engineering that made the programme possible.

However, for Usherwood, it was less about recognition and more about proving how small projects can succeed when they combine traditional engineering skills with modern manufacturing techniques. “The engineering, and the way the ice cube behaved, spoke for itself,” he says. “It did the job it was required to do, and then some.”