Articles

The stickman portrait, with its wide toothy grin, was the kind of improvisation that has served Rohde well, even at the North Pole.

Rohde, 33, calls what he does on polar expeditions “MacGyvering,” in reference to the American action television series. But that’s being far too modest. He and other engineers on research missions like MOSAiC (the largest polar expedition in history) are the bridge between science and its application in a world desperate to better understand climate change.

Rohde returned from his second MOSAiC posting last October. While away in those frozen lands, he endured temperatures down to -35º C, trying to twist a screwdriver or remove an SD card while wearing the snow version of a space suit.

Extreme challenges

“Everything is so much slower,” he explains. “What usually takes an hour at the institute can take three to four hours, or even a day. If something is frozen, you have to get rid of the ice. What makes it extreme is there’s no way to escape it. You’re there. There’s no popping out to the hardware store. You have to deal with it.”

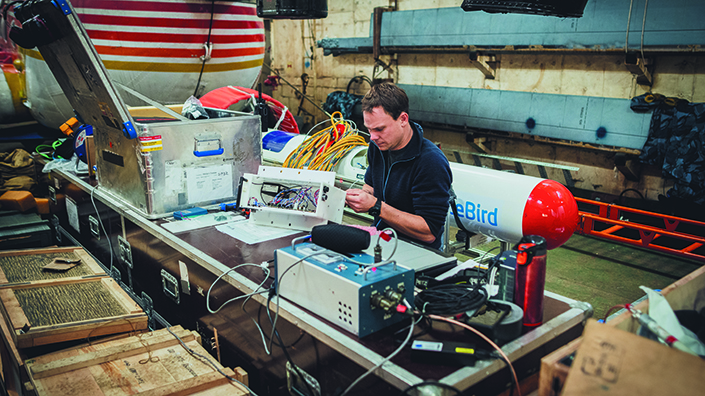

Jan Rohde working on the EM-Bird sensor aboard the Akademik Federov

Rohde remembers a time when he and a small team were flown away from their ship to set up a helicopter landing site. The moment they were dropped off, the silence fell. After weeks on board a busy science vessel, they were alone. Around them was nothing but snow and polar ridges. Beneath them was a slow-moving ice raft, masquerading as solid land. Beyond the ridges and the white haze were polar bears.

While two crew members kept watch, and another busied himself with a research instrument, Rohde got to work planting eight reflective wooden poles into the ice. But there was a problem. The drill bit was too narrow. The poles didn’t fit. Back at a lab, fixing this would be as easy as fetching a new drill bit. But here he had to use what he had packed. There was no plan B. And the helicopter would be back in about an hour to pick them up, trying to catch the little daylight left.

Rohde reached for his Leatherman multitool and hacked at the wood. It wouldn’t be perfect, but it was the perfect improvisation.

Whether he’s in the field or back at the Sea Ice Physics Unit of the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, west of Hamburg in Germany, Rohde’s job is all about engineering solutions. His focus is on the instruments used to study ice – great big chunks of it – and how this frozen sea water affects climate systems.

The EM-Bird is an airborne sensor

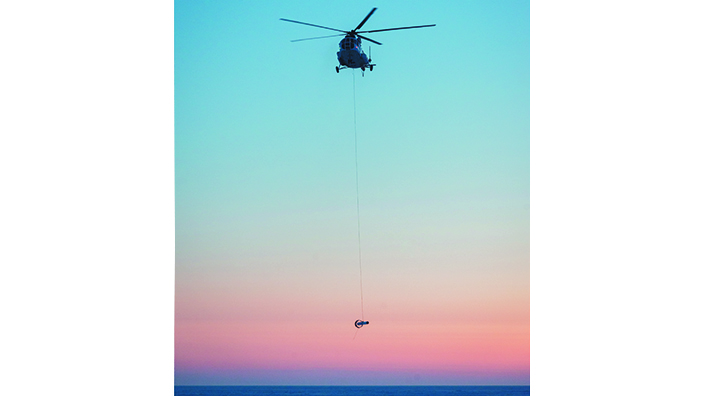

He builds and fixes machines used in this important research and, while on expeditions, deploys or pilots them. From torpedo-looking sensors like the EM-Bird, an electromagnetic instrument flown under the belly of a helicopter to measure ice thickness, to autonomous buoys, he works with them all. It’s like poking and prodding a piece of ice from every possible direction, Rohde jokes. Sometimes it takes a complex remotely operated submarine and sometimes it’s just about drilling a hole and using a metre stick. One of his big projects is to develop a new-generation EM-Bird, which will need to perform in extreme environments.

Motivating force

“That’s the purpose of engineering. To make things people can use,” he says.

Rohde has been on over half a dozen expeditions. Now he’s back home. “Seeing that there’s interest in our work motivates me,” says Rohde during our Skype interview, his stickman avatar still grinning on the screen. “The universe gave me an opportunity to be involved in this mix of technology and the environment. To do my part. And to experience the full spectrum of engineering work.”

Want the best engineering stories delivered straight to your inbox? The Professional Engineering newsletter gives you vital updates on the most cutting-edge engineering and exciting new job opportunities. To sign up, click here.

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.