The construction site is eerily quiet. No workers rush around in hard hats hefting tools or materials, no scaffold skeleton stands against the clear winter sky. Instead a single robot arm moves back and forth with precise, jerky movements. A nozzle at its end lays down a gloopy grey mixture of concrete in a complex swirling pattern.

At first it is unclear what is being made but as time passes the structure begins to reveal itself. It is a house. Just a day later, the building is complete – a single-storey home in a striking propeller shape.

This house, the first to be printed in one shot of 24 hours, was built earlier this year by San Francisco-based start-up Apis Cor in a town near Moscow. The feat was a game changer because until then 3D-printed structures had been comparatively expensive one-offs. Apis Cor’s breakthrough has opened the floodgates to 3D-printed (3DP) construction on commercial scales that can compete with – and beat – traditional building methods.

And there is more. Dutch firm MX3D is using a combination of MIG welders and robot arms to print large metal structures faster and cheaper than ever before. British company AI Build is using artificial intelligence to improve the speed and reliability of 3DP construction. And Cazza claims it will soon build the world’s first 3D-printed skyscraper in Dubai.

3D-printing technology offers tantalising benefits for construction firms. It promises to be cheaper, greener and faster than traditional methods, and could have far-reaching benefits in the developing world. Challenges remain, but technologies such as artificial intelligence are helping to overcome some of the practical and regulatory hurdles. Will we soon be living in a printed world?

According to Italian inventor Enrico Dini, everyone seems to want part of the action. “It is very close to being commercially viable,” says Dini, who a decade ago was the first person to create a 3D printer capable of producing buildings. “The big players – HP, Microsoft, Amazon, and all the big streams of the construction industry from the construction and cement companies to the architects and contractors – everybody has to be part of this dream and must strategically say ‘we must open a 3D printing division, we have to be part of this game’.”

3DP pioneer Enrico Dino dreams of a landscape filled with fantastic shapes (Credit: D-Shape)

Cheaper construction

Building a house in one go in just 24 hours with just one machine is clearly a huge step towards the goal of commercial viability. Apis Cor has broken down the numbers. Its house is a single-storey structure of 38m2 built at a cost of $10,134, including the foundation, inner and outer finishing, wall insulation and windows. This, according to the firm, makes its technique 70% more economic than traditional labour- and material-intensive methods.

The race to print buildings on a commercial scale is on, and other start-ups are close on the heels of Apis Cor. One problem that has proved a stumbling block to 3D-printed construction has been the unpredictable nature of building materials. Small mistakes can be magnified into large structural failures by the additive printing process, so slowing down overall manufacturing.

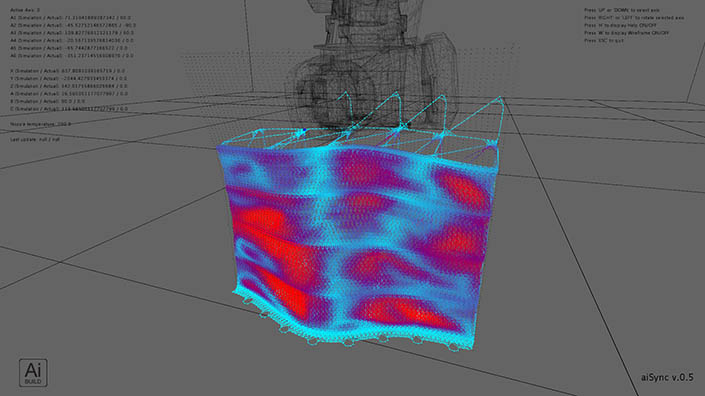

But now AI Build is combining artificial intelligence with robotics to create machines that can effectively see what they are printing and respond to their mistakes. “We give robots the ability to see and sense the environment, for them to be able to make decisions on the fly by processing this data in real time,” says Dağhan Çam, co-founder and chief executive of AI Build. “This is a paradigm shift from blind automation to autonomous manufacturing which makes the system resistant to unpredictable conditions on a construction site or a factory floor.”

AI Build’s first commissioned structure built last autumn cost just a fraction of what a competitor quoted, adds Çam. The use of AI allowed the company to print the intricate structure (the Daedalus Pavilion for the GPU Technology Conference in Amsterdam) in just 15 days.

One-shot printing is the holy grail of 3D-printed construction. Another team aiming to achieve it is the Italy-based WASP project. Its 12m-high Big Delta Wasp prints buildings within a large frame-like structure, using a movable nozzle to extrude the construction material. In WASP’s case this ‘ink’ can be any fluid, dense material such as concrete or, crucially, clay and mud.

The ability to print with clay and mud is important because the vision of WASP’s founder, Massimo Moretti, was to build cheap houses in poor countries with ready-to-hand materials. “One of the key points is to be able to use all the resources that you can find in place,” says WASP’s Davide Neri.

This even includes the energy for the machine itself, which comes with its own solar power pack, enabling it to be used off-grid anywhere in the world. Although large, the machine is designed to be easily transportable and can be erected on-site by two people.

WASP has successfully printed its first prototype house (or ‘large architectural volume’ as it was forced to call it to avoid prohibitive Italian building regulations) using mud and concrete.

The team found that during summer it would take a week to build a full house in optimal weather conditions. And all for a cost of just €48. Neri is confident that Big Delta Wasp will be available to start shipping to customers within six months. It will be part of WASP’s Maker Economy Starter Kit, a shipping container including the Big Delta Wasp and a range of smaller 3D printers, allowing users not only to print their own house but all the furniture and goods to go inside it.

Tim Geurtjens of MX3D (in blue) thinks 3D printing can open new doors for architects (Credit: MX3D)

Skilled robots

Meanwhile the godfather of 3DP construction, Enrico Dini, has not been idle. Dini’s own printer, D-Shape, built the world’s first 3D-printed bridge earlier this year in Madrid. The 12m pedestrian bridge, spanning a stream in a park, was printed from micro-refined concrete by the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia.

Aside from building bridges, Dini has a project lined up to build a “super-standing iconic building” for the Dubai Expo 2020. He is also working with a large London-based architectural firm to design an entire development of 3D-printed buildings. He even plans to use 3D-printed ‘trees’ topped with solar panels to reclaim land from the desert.

But perhaps his most important project is working with a contractor in Dubai to produce, not one-shot printed houses like those of Apis Cor or WASP, but smaller building blocks from which bigger structures can be assembled. “We’re trying on the one hand to grow step by step, and on the other hand to make the big jump up to big business,” says Dini.

It seems that the rise and rise of 3DP construction is inevitable. The question now is perhaps less about when it will be achieved but how the technology should be used. For firms such as Apis Cor and WASP the goal is fast, affordable housing. But for others such as Tim Geurtjens, the co-founder of MX3D, using 3D-printing construction techniques to build cheap, mass-produced houses shouldn’t even be the discussion. Instead it should be, says Geurtjens, “What can we do with 3D printing that we were never able to do before?”

Geurtjens’ own MIG-welding robots are currently printing a steel bridge to cross a canal in Amsterdam. He sees the future of 3D-printing construction more in terms of similar one-off iconic projects. In terms of mass production, he thinks 3DP construction should be seeking collaboration rather than domination of the market. He sees the future as one of old and new techniques working in harmony – production-line factories with 3D printers making parts, or robots working on location on parts of buildings that require customisation – the traditional role of the skilled worker.

Ironically, in a field that always inspires talk of futuristic visions, 3D-printing construction might lead to a renaissance of traditional values in the mass marketplace – decoration, craft skills, non-standardisation. “In the last 50 years, decoration has completely gone out of architecture,” says Geurtjens. “It’s too expensive – you need a skilled craftsman who needs to put a lot of time into the detail. For a robot it doesn’t matter how complex things are. From that perspective, I think the aesthetics in the construction world could change a lot.”

Companies like AI Build want to use digital technology to make construction cheaper and safer in the future (Credit: AI Build)

Companies like AI Build want to use digital technology to make construction cheaper and safer in the future (Credit: AI Build)

Dini agrees. When he was first working on creating D-Shape, he used to daydream about sailing along Sardinia’s Costa Smeralda, watching the rocks on the shoreline and then noticing that some of them weren’t rocks at all but beautiful 3D-printed buildings that had been crafted to blend in seamlessly with the landscape. Dini sees 3DP construction as a chance to bring beauty back into building. “I’m an Italian,” he says. “For me beauty is not an optional in building construction. I truly believe that 3D printing might be one means to achieve beauty.”

Dini’s vision is of buildings so in tune with their environment that they ‘bed in’ and age with the landscape in a way that only the most timeless architecture can.

“My land, Tuscany, is beautiful,” he says, “because for centuries buildings have been built with the materials that came from the land, so a building should go back to the land as it ages – that is beautiful. If we interpret 3D printing as a matter of mass production, of recycling crushed cement and demolition rejects that you extrude with polymers, cables, wires – that is fine, but it’s not beautiful.”

Apis Cor used 3D printing to go from foundations (shown here) to a completed house near Moscow in just a day (Credit: Apis Cor)

Dubai: a haven for 3D printing

In 2016 Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai, launched the Dubai 3D Printing Strategy, aiming to make the city a world hub for the technology.

One of the strategy’s main aims is to see 25% of buildings in Dubai constructed using 3D-printing technology by 2030.

The strategy was followed not long after by the construction in Dubai of the world's first fully-functional 3D-printed office building, put up by a robotic arm in 17 days.

The city in the United Arab Emirates has since proved something of a Mecca for 3DP technology, with more than 700 companies involved in 3D printing.

One of these is Cazza, a US start-up co-founded by 19-year-old entrepreneur Chris Kelsey. Kelsey moved the company from the US to Dubai after being invited to showcase his technology. Now he claims to be planning the world’s first 3D-printed skyscraper using a bigger version of the company’s Minitank, a 3D-printing crane that can produce buildings up to three storeys high.

Lead image credit: MX3D